|

READ this BLOG if you don't have the patience to read my blog!  I’ve been trying to remain silent and prayerful about the violence unfolding in Israel and Gaza. These are not my people. I cannot possibly understand the generational pain on both sides. I am overwhelmed by the cycle of oppression and violence that is the story of both Palestinians and Israelis.  And yet these are my people. Why? Because they are God’s beloved people. I cannot turn away from hearing the news that regular folks were stolen from their homes and held captive. I cannot turn away from the images of entire neighborhoods destroyed. So much death and violence and destruction and more generational trauma. I find myself silent and prayerful and hopeless. Yesterday I hesitantly reached out to my Jewish spirit-sister. Her ministry is one of healing, mine leading a church. Her particular Jewish faith infuses her being in a fundamental and natural way. I can only aspire to a particular Christian faith that runs through my being as naturally as her Jewish faith does. She is also a progressive Jew (my words, not hers). She, like me, is very willing to laugh at her tradition, speak about its shortcomings, learn from other traditions, and examine her blind spots. She is particularly Jewish, but not limited by her tradition. I am particularly Christian, because as I say often, I was born into a northern european family. I have more in common with my Jewish spirit-sister than I do with most Christians.

And yet I did not call her, text her, ask her how she was when I learned about the attacks on Saturday night. She has beloved friends in Israel. I know this. I remained silent. I didn’t know what to say. ME!? The person who always says too much. I was angry at this cycle of violence. I wanted to affix blame somewhere, but where? And I did not reach out to my dear friend. Yesterday I wrote to my friend something earnest, but still reserved, not filled with my usual head-on-love. I felt sure I had no right to “weigh in” on the violence. I simply told her I was praying. I concluded my message to her, “praying for the individual souls who are connected in a web of history too painful for me to understand. In particular I am praying for those you love there. And I am praying for you.” My silence was short sighted. I didn’t need to explain for whom and how I was praying. She only needs me to help carry the burden of praying for an entire part of the world marred in violence. She needed to know I cared. She needed to know I hurt for her. She needed to know she was not alone. She needed to know I loved her and therefore I loved those she loved. I share her response because it was the splash of cold water I needed and perhaps you need too. “Thanks for reaching out, sharing your prayers. It is a hard time on so many levels and yet it helps when our non-Jewish friends reach out in support. Here is a link to a blog that goes into this more.” Read this blog. READ IT! And reach out to your Jewish friends. Reach out to your Palestinian friends. Reach out. Do not remain silent. Also do not assume you understand the depths of this conflict. Hold on to hope for peace. Above all right now, care for those who are hurting right in your backyard--for the many Jewish and Palestinian American friends who do not need more political rhetoric or petitions or statements. They simply need our prayers and love.

0 Comments

Shannon and I became friends our first year at Colgate. We were roommates for the following three years. After Colgate, Shannon moved to San Francisco. I stayed on the East Coast. For 25 years we have called each other and talked while driving children to school or from our offices or while folding laundry. We have visited every opportunity we’ve had. We have stood up for each other at weddings, shared our children’s baptismal dress, sent Christmas packages, taken our families camping, and even helped each other through knee buckling crises. We are family. Colgate is our home. I grew up in Buffalo, just four hours away from Colgate University. All four of my grandparents had earned college degrees. My college fund was begun in my first year of life. Before my senior year, even as a fourth child in my family, my parents took me on an endless six day road trip to see a variety of schools. You can go anywhere you get in was what I heard often on that trip. Shannon grew up across the country in Southern California. She was the first in her family to head off to college. There was no college fund. Shannon was the high school super star. Many of her fellow classmates never dreamed of college. Her high school sent one student--Shannon--east to pursue a college degree. She packed her bags and flew across the country with no idea of what awaited: long, dark winters, demanding classes, lots of classmates who were also high school superstars, and most overwhelming, tuition payments. College is a blessedly awkward and liberating time of transition from childhood to semi-adulthood. My first year at Colgate was filled with beautiful challenges. There were days I felt overwhelmed and homesick for sure, but I discovered how ready I was for the next chapter of my life. Colgate helped me become. And my parents happily footed the bill. Shannon’s adjustment practically (how do you dress for winter?), socially (these east coasters are different), academically (I’ve never written a research paper in my life) and emotionally (how do I manage a relationship with recently divorced parents), were monumental to say the least. And amazingly, still, Shannon thrived. She faced these adjustments with fierce determination and confidence. Colgate helped Shannon become her best self. But there was one thing out of Shannon’s control: tuition payments. Every semester would begin with Shannon at the registrar's office discovering once again why she was not registered for class. Her tuition bill was yet again unpaid. What would follow was a painful phone call asking a parent to pay the small remainder of her account. Shannon took a great deal of responsibility for her own tuition through scholarships, work-study, and loans. The registrar would assure Shannon she could begin her classes, even though she was not “officially registered.” She would usually find her way to the financial aid office in tears. Every year, Shannon doggedly took on more financial responsibility for her own future.  Just this week, Shannon honored me at our 25th Colgate Reunion in front of our entire class. She has personally endowed a scholarship in my name. The Abigail A. Henrich Scholarship is to be used entirely for students with demonstrated financial need. The irony and beauty of this scholarship is not lost on me. I have been unable to think of little else these past few days as I have processed this monumental honor. Shannon’s scholarship celebrates everything about our friendship. The very presentation of this scholarship at our class dinner celebrated the story of our becoming at Colgate, where our lives permanently wove together. Yet how am I, the one whose tuition was fully funded by my family, to have my name on this scholarship? I never paid a student loan in my life. I never worried about how much money I would make as a pastor because I had no debt to speak of. It seems the scholarship should be named The Abby and Shannon Friendship Scholarship, or the Registrar's Office Scholarship since they always lovingly found a way to help Shannon each semester, or the Thank God for Savvy Financial Aid Officers scholarship. Why should it be named for me? I have no answer to this question. Shannon would answer it is because my friendship set her forth on her path, but I am certain that our friendship existed because of the environment--Colgate--in which it was rooted. Colgate is a powerfully transformative place. My Colgate liberal arts education is my most prized possession. My friendship with Shannon is forever life-giving. For now, I will set aside my question and my shock that there is a scholarship in my name, and instead rest in deep thanksgiving. Thank you Colgate. Thank you Shannon.  I wrote the below blog 10 years ago for Mother's Day. On this complicated holiday, that I vehemently despise since I find it to be exclusionary, heteronormative, and sneakily misogynistic, I wanted to honor my own journey to motherhood. I also wanted to honor the reality that rarely is the road to parenthood simple. In fact, I have discovered over these past ten years that NOTHING about parenthood is simple. 10 years later I find myself struggling with new complications: How do you raises teenagers who want less emotional connection, but still need it? (If you have a answer, please let me know.) How do you honor your children's autonomy? Why do I enjoy loving my two year old goddaughter more than teenagers? Should I feel guilty about this? I have no insightful blog about these latest questions, but beow in my honest story. JOURNEY TO MOTHERHOOD, written May 2012 The vast majority of my sexual education focused on how to keep from getting pregnant, so much so that I naively assumed that to get pregnant you need only to have unprotected sex once. Without revealing any embarrassing details, my husband and I truly thought I would be pregnant in a month’s time the summer after I received my graduate degree. We calculated on our hands more than once that our baby would be arriving sometime in March. But my period came after that first month of trying; I cried and immediately alleged that there was something wrong in our technique. Then the next period came; I sobbed and assured my husband with my typical dramatic flair that I was ready to adopt. After two missed attempts, getting pregnant became something to accomplish. The process was not to be enjoyed. I peed on sticks, prayed, raised my feet over my head, talked to every recently pregnant woman I could find, and waited in fear. So it was with great joy and relief that after six months of trying I discovered I was pregnant the second week of my very first pastorate. We glowed with anticipation and again naively assumed that everything would be smooth sailing—we were pregnant now. All we had to do was wait nine months for the arrival of our baby. A week before my ordination, while being questioned on the floor of presbytery, I knew I was miscarrying at ten weeks. The sight of blood before the presbytery meeting lead to a call to my midwives, yet I knew I could not miss that night’s meeting. My ordination depended on it. I stood before a group of elders and pastors who asked me highly controversial theological questions about my position on atonement and salvation, but I remember only thinking about where I could find a bathroom after so I could check if there was more blood spotting my underwear. The next day an ultrasound stole the promise of that sweet child from us. Our final innocence, as those who deeply yearned for children of our own, was over. Fear laced our life as parents from then on. I have never forgotten our first baby, long forgotten by the world, nor the sheer uncomplicated joy accompanying the promise of that first positive pregnancy test. Almost eleven years later, I cannot bring myself to throw away the medical records that document my miscarriage; they are my only physical reminder of our first child. Our first remains unnamed. I am not sure why we have been unable to name our child. Perhaps because it still feels like a dream, the medical records the only thing confirming that it did really happen. Or perhaps because we never had a strong sense whether our promised child was a boy or girl. Yet still, this child’s brief life has embedded itself deep into the fabric of our life together as parents. **** Silent waiting ruled our lives in our four bedroom parsonage. We couldn’t bear to wait, yet we had no other alternative. Again we found ourselves consumed by the process of getting pregnant. Each month our waiting was laced with hope, but every period plunged us back into sorrow and mourning and despair. After dinner, with no children to tend to, with only work awaiting us, we would fill up the empty waiting with an ongoing game of gin rummy. We kept our grief and loneliness at bay by staying in constant motion. Then we got a dog. We needed something to love. And then the testing began—painful dyes injected into tubes, brown paper bags and dirty magazines, and results. At twenty-six years of age I began IVF—in vitro fertilization. There were waiting rooms filled with silent women, waiting for blood work, waiting for consults with specialists in white coats, and waiting for the defining test result. Occasionally a stricken partner waited alongside us. There were needles and vials upon vials of hormones, delivered efficiently by Federal Express. There were the evenings my husband’s face, gripped with steely resolution, stuck a needle deep into my hip, I would sob in pain, only to run off to a deacons’ meeting after a band-aid was applied. We waited in silence, hoping, fearing the worst, and preparing for the unthinkable, another round of shots and harvesting and waiting. But it worked. At five weeks gestation we saw the fluttering heart of our baby. Still we were forced to wait. We could not embrace the promise of that undulating muscle until the crucial marker of thirteen weeks. We had been deceived before. Thankfully, with time that tiny beating heart grew into the strong heart of a screaming ten pound baby boy. I wish my painful story of conception and gestation ended here, but the joy of pregnancy has eluded me. My third pregnancy ended in miscarriage at thirteen weeks on Ash Wednesday, after announcing to my entire congregation the Sunday prior that I was pregnant. This time we named our baby—Kasia. On a warm Spring day we planted summer bulbs in her memory, our young son wading in the water nearby. I spent my fourth pregnancy reeling in terror, holding my breath between each revealing gesture of my baby’s limbs within the womb, sure that the baby, even at twenty weeks, would die before I had a chance to hold it. This pregnancy, which produced another ten pound baby boy, is mostly lost to me. I can only remember the terror. I am not sure if I ever experienced any joy until my second son was six weeks old, nursing calmly and happily at my breast. **** No one ever told me how difficult it would be. No one—not my mother, or my aunts, or my grandmothers, or the women whose children I cared for, no one. After I lost my third child, I awoke in the middle of the night, unable to breathe, a crushing weight on my chest, and the clear resolution that I could never have another child. I was certain in that still dark room that the pain of pregnancy would keep me—the teenager who watched a family of five and did their dishes without breaking a sweat, the college student who babysat every Friday night instead of going out, the young bride who had decided with her beloved mate that they would raise four children together—from ever having more than one child. The fear of conception and gestation suffocated all my confidence and all my hope. I remember one evening in particular, after our first child was born: I hid away in our bedroom and wept. I was utterly exhausted by my dashed hopes and terrified by the chance of more loss. I thought if I wept alone I could ironically protect myself, as if in hiding my fear, no one, including myself would know how really bad it was. I understand now, that I was in essence rejecting the very vulnerability that parenthood entails. Yet I did not grieve alone; I grieved in the presence of loving community. Grace encircled me with the stories of many gentle people, mostly women, but also men, who had lost children as well. Their stories were ones of pain and grief, but also of hope, survival, and sometimes children. They were the stories of twelve-week-old twin girls, a twenty-five- week old baby girl still referred to as an angel by her parents, a still birth boy, a still birth first, another set of twins, five miscarriages in a row before a healthy baby was born. These stories I laid beside mine. As I entangled my own grief, I came to understand that these stories were the unavoidable stories of conception, gestation, and birth. They are the stories of parenthood. ***** Sadly, my story continues. After my second son was two I miscarried for a third time. I was placed in the high-risk pregnancy category. They even performed an autopsy of sorts on our sweet 13 week in utero baby girl who we named Elise. I began a regiment of antidepressants and weekly therapy because I could no longer fight the grief and fear on my own. The good news is that somehow, my call to motherhood was so undeniable, I found enough courage to try again. The trying was fraught with waiting and wondering if we would ever get pregnant again. And when finally I did get pregnant, my anxiety spiked and my antidepressant prescription increased from 50 grams to 100 grams. At the end of that successful nine month gestation, I had a perfectly healthy baby girl. And three days later I was greeted with debilitating postpartum depression. I do not want to make light of postpartum depression; it was horrible. Yet I was fortunate that I received medical help immediately and responded positively to medication. For me, more than anything, postpartum seemed like a slap in the face after the exhausting effort I had put forward to have a third child. I remember very little of my daughter’s first six months of life. Now that she is three this seems to bother me less. Who remembers the blur of sleepless nursing anyhow? **** My children are older now; their bodies stretch out, filling their beds, relaxed in sleep. Some days I barely remember how painfully I yearned for their presence. Some days I even desire a break from all the work that they generate —lunch boxes, laundry, speech therapy appointments, lacrosse games, snit fits, dishes. Every mother’s day, I remember with clarity what it was like to yearn desperately to be a mother. Every mother’s day I relish the homemade gifts and earnest attempts at breakfast in bed. And every mother’s day I remember there are many women who feel locked out of the “club” as I smell my children’s hair as they climb into bed with me. **** I have not one profound thing to say—not one thing that will make sense of any of this pain or longing or unfairness. Some of us end up as mothers, others wait, others mothers more children than ever desired, and still others long for someone with whom to share motherhood. I pray for all and carry each woman in my heart. Recently our community lost a beloved member. It was traumatic in nature and unexpected. As a community, and individually as a pastor, we have learned much about grief and trauma. I want to offer a101 basic this-is-what-you-do-if-you-find-yourself-in-a-similiar-situation. I pray you don’t need it. BEFORE ANYTHING ELSE: If the body is in the home, call the police asap if you are there or not. The police are equipped to deal with these situations. #1 Alert all the Professionals connected to the family/loved ones of the deceased: Who might those be: -General Practitioners, Pediatricians, Psychologists, etc You do not need for them to tell you anything, you are simply passing along information, so if anyone complains about HIPPA, ignore them. -Guidance Counselors for school aged children and youth -Police if appropriate -Social Worker if there is one With each and everyone of these professionals use the word traumatic death. #2 Help the family make immediate arrangements. What does this entail? -Hire a trusted funeral director. If you don’t know who that might be in the area, call a local church. All churches have relationships with their local funeral directors. -Use the words traumatic death with the funeral director. The funeral director is a professional and will understand the care needed. -Enlist community support to pay for the funeral expenses. -If any family member asks to see the body, strongly encourage them to wait, until they have spoken to a mental health professional. Often, in these times, seeing the deceased body is of little or no comfort. -When speaking with the family, acknowledge the horrible loss, weep with the weeping, remember with them, laugh when appropriate. Be helpful. Don’t be avoidant, but don’t be afraid to make small talk--you can’t talk about the tragedy all the time, sometimes you just end up talking about the weather. All the conversation is comforting. #3 Call family and friends of the deceased for the survivors. Often this is too difficult for those who have survived. Make it simple and brief: I am very sorry to tell you that x has died. When questions are asked, only offer what the family is comfortable sharing. No matter what, gorey details are NOT needed or appropriate. Yet also be honest and frank. Secrets are not helpful. You can also send texts to preferal people because it is too much too call more than 20 people. The text again can be brief and to the point. Explain why you are texting simply by saying there are too many people to contact. #4 Call a Mental Health Professional Don’t know where to start, ask any mental health professional or medical doctor. What you need from the Mental Health Professional:

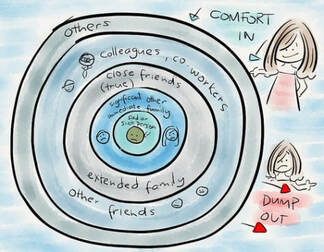

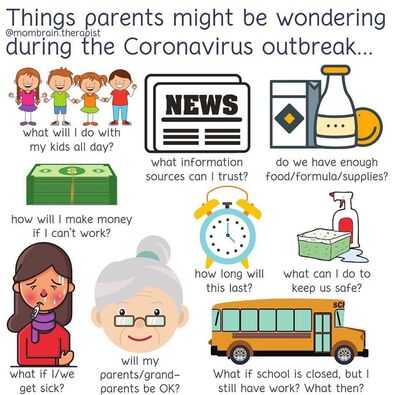

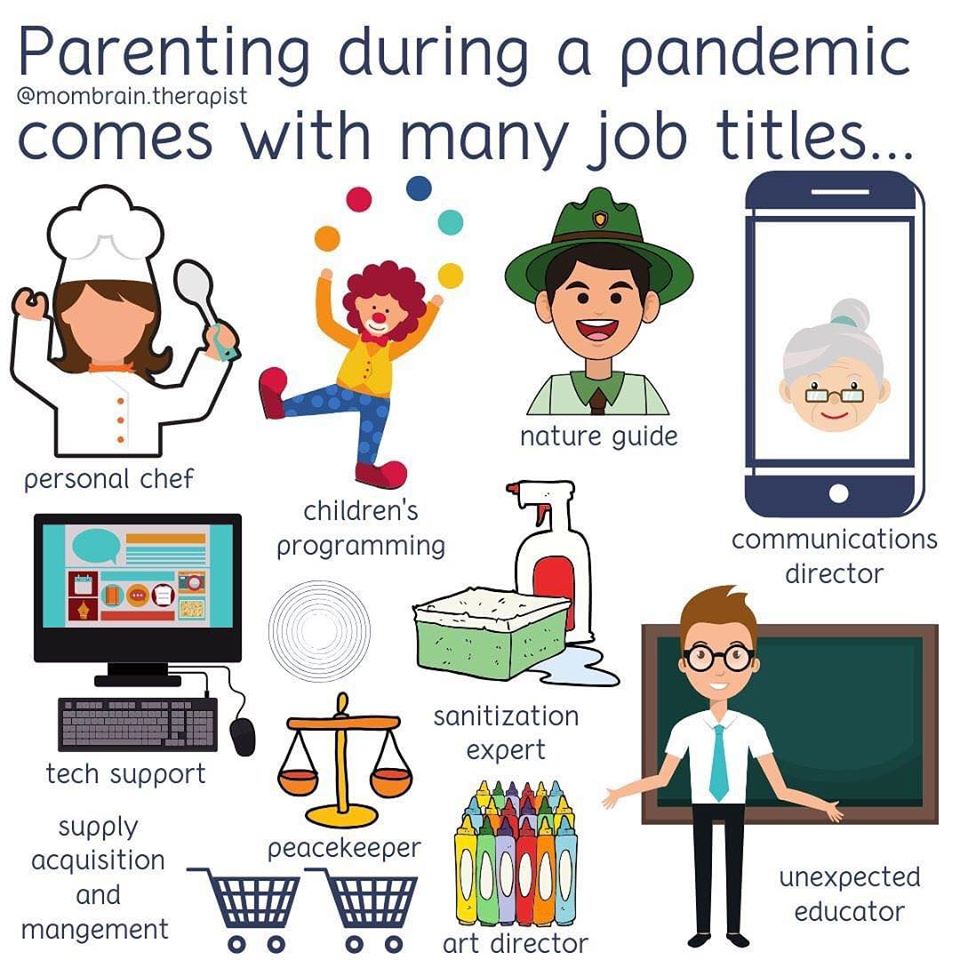

#5 Practical Care Practical Care makes a difference. For example, does the family have a dog? Can different people sign up to walk the dog for the first few weeks? Can folks come and help with dishes? Set up a meal train? These basic needs met is a reminder to those in shock and grief that life continues and that people will help them continue. Every meal received is a palpable reminder of God’s love. #6 The Actual Funeral Service -Ask professionals, such as social workers, clergy, and others who do not know the deceased, to come and observe. Why? Because people with fresh eyes who are not overwhelmed with grief need to observe the gathered community for those who might be in crisis. You will know best who these folks are. -Create a table with all the stuff: tissues, water, life savers, mints, fidgets. -Make sure someone is welcoming everyone at the door. -If you are the religious leader and you were close to the deceased, ask your closest clergy friends to help you lead the service. This is imperative even if you think you don’t need help. Trust me. -Ask people in the community who are on the fringe and might not know the deceased as well just to come and bear witness, to help hold the pain for those grieving. This makes more of a difference than you can imagine. -Make space for joy through a remembrance of pictures and or stories. If possible, gather with food. These “normal” moments are healing for many. Don’t be afraid to laugh. Trauma does not eclipse joy.  #6 Love & Care in, Grief (Dump) Out. *See Image* Imagine those who knew the deceased (or as the picture labels below the “sad or sick person”) creating concentric circles around them. Those closest emotionally, or whose lives were the most intertwined with the deceased, are in the inner circle, whereas others are further out, depending on their relationship. The idea is simple: as much love and comfort should move into the center of the circle helping to spread (or dump)the grief out. This does not mean that those who are grieving will all of a sudden be “grief free.” Instead the idea is that others help them hold the unbearable amount of grief they must process. As a community we found this concept very helpful to us as we envisioned just what it was we were doing.  I have a few thoughts to share about education during this time of COVID-19 homeschooling isolation hell (um… did I say hell? yes!). I’ve decided to share these thoughts with you (that would be any of you who happen across this blog). My youngest child is now 10. I’ve lived through preschool years and almost completed the elementary school years. This does not make me wise. It simply means I might have a bit more experience than some. I’m a mom who has lived through the complicated educational needs of three very different children. That said, I still parent most of the time with a “let’s see what sticks'' approach, especially now in quarantine. Second, as a progressive christian minister, I am responsible for the spiritual education of children. Between my experiences covid-churchschooling and covid-homeschooling, I realized I had some things to say that might be helpful. The following is the Abby maybe-helpful, maybe-not list, to guide you through and maybe beyond quarantine as your children’s educators:

The struggle is real! This is so hard. Balancing work and teaching and parenting. Balancing our own emotions in this uncertain time while being present to our children. Oy vey! (This is an excellent yiddish alternative to my favorite F word since we aren't suppose to be using that word so much now that the kids are around). So please be grace-filled toward yourself, your children, your community, and again and again to yourself. Pandemics are difficult. Spending a day on the couch watching movies is okay too.

MANY thanks to @mombrain.therapist for these super helpful info-graphics. I was taught to be a nice girl. You know, nice and polite and quiet. It didn’t stick, thank God. I’m connected, but not nice. I genuinely care about the people in my life. I pray for people in checkout lines while I wait. Really. I’ll also tell the people in my life the hard truth, like they need to end that broken relationship. Nice is surface. Connection is deep. Polite isn’t my gig. Caring is. I’ll show up at your house with dinner after you’ve had a baby, tell you all the gruesome facts about postpartum, laugh with you, cry with you, and go out to purchase you some hemorrhoid spray if you need it. Ms. Manners would have me leave a nice note with food at the door. This full postpartum disclosure is definitely not polite by my mother’s standards. I talk about everything, mixed company or not. By the way, what is mixed company nowadays, anyhow? I AM NOT QUIET. Outspoken? Without question. I am usually the loudest person in a room. I’m a preacher for goodness sakes! Stop telling me to be quiet unless someone is sleeping. I could have been that nice girl, maybe, but nice was too small and tidy a cage. I tried occasionally to fit my big personality into that cage, but it never fit. It always burst out. . *** Nancy Pelosi was probably taught to be a nice girl too. Yes, she grew up attending political rallies and learning the importance of social justice. Yet as the youngest of seven and the only daughter, who attended an all girls Catholic school, I’m certain she was exposed to the cult of nice. Ripping up Trump’s state of the union speech on prime time TV was not “nice.” It was not polite. Ironically, it was a very quiet LOUD action. It was angry. Here are some facts (not alternative facts, but real facts):

Trump and Limbaugh rip up humans. Nancy Pelosi ripped up a speech. That’s it. Her anger was contained. She was silent. She did not interrupt the state of the union. Nevertheless, her actions were labeled as childish, bitter, and classless by the same people who have embraced the hateful speech of the man who holds the highest office in the nation. Is this because they are hypocrites? Clearly. But it’s also because as a culture we do not tolerate angry women. Why are we not applauding Nancy Pelosi for keeping her anger in check for as long as she did in this hateful new political landscape? How did she keep from screaming against a bigot who practices cruel, sexism, racism, and nationalism? We should applaud her for appropriately and publicly revealing her anger toward not only a president, but also a senate that has embraced a corrupt president. If she were a man we would have applauded her. Men are allowed to prophesy, angrily. If Nancy Pelosi had a penis, she would have been celebrated as a powerful leader instead of a childish, bitter woman. But Nancy Pelosi isn’t bitter at men, she’s angry at injustice. And she should be. Jesus wants her to be. We just don’t know how to handle anger in those we have deemed inhuman and undeserving: people of color, women, LGBTQ+, immigrants, and others. White men, on the other hand, are allowed to be angry. You need look no further than Brett Kavanaugh’s rage or Lindsey Graham's theatrics during the confirmation hearings. There is also the POTUS who tweetstorms his fury daily. But Nancy Pelosi’s controlled, visible anger at the State of the Union riled the patriarchy because America can’t make room for women’s unabashed anger in our chauvinist culture. America likes nice girls, not powerful, bold women who show up ready to fight. *** Like Nancy, as a deeply connected christian, I cannot ignore the plight of others. Whole groups of people in our country are struggling with basic human rights such as health care, food, shelter, and education, due to the inhumane policies of our current administration. Nice can turn away from their suffering, but Nancy can’t, and I can’t. As a minister confronted daily with the needs of the least of God’s children, during an administration that dismisses and often mocks God’s beloved people, my anger rightfully rises. It rises because I am a disciple of Jesus. May yours rise as well.  My high school dean silenced me as a 17 year old girl with the exact words, “We already know what you think.” I had gathered a group of female classmates to tell her that the physics teacher was raping our classmate. She was annoyed with me, troublemaker that I am. You can learn more of my story in this blog. When the truth of my allegations came out 30 years later, after an extensive investigation by a law firm, she lost her job at my high school. There had been a culture of abuse, the law firm determined, and the dean had been complicit, so the school let her go.abbyhenrich.weebly.com/community/archives/10-2017 She was immediately hired at a prestigious college. What is the way forward after #MeToo? Should my dean’s career be ruined indefinitely for what she said to me 25 years ago and for her complicity in a culture of abuse and her willful denial? Or should she be forgiven and allowed to continue her work in education? These questions are important: How we heal as individuals and as a society is the significant work before us in this new #MeToo world. Let me begin by telling you what is NOT helpful in this healing process:

What IS helpful? I can only answer this question from my very individual perspective. Recently I have been learning about restorative justice as an alternative to our criminal justice system. At the heart of restorative justice is the involvement of the victim. If someone were to ask me what would restore justice to me after the #MeToo experience I endured at Nichols, I believe I have a clear answer:

That’s it. Face to face listening and an apology. From my perspective this is a simple request. Would it be emotionally exhausting? Yes. Would they be incredibly brave to do it? Yes. Without question. Would it be worth it? I deeply believe it would be. There is no way forward without reconciliation. Reconciliation takes telling and listening. It takes acknowledging pain, asking for forgiveness and offering forgiveness. It takes facing the past together and looking forward to a future. It takes collectively struggling for a new way. I also wonder if I were to come face to face with my dean and headmaster, if we could grieve together for the people we were, trapped in a terrible system. They might have been as trapped as I was and in need of just as much healing. I refuse to accept that they are morally bankrupt humans. Instead, I would guess that both are deeply troubled by what happened and desire a way forward. If I were granted an opportunity for restorative justice with my dean, how would that change my perception of her new position? If she was brave enough to engage with me in authentic conversation and listen with an open heart to my story, I would speak positively about her new beginning. I would remind others that we cannot judge someone solely on their past, and that together, as a community, we must move forward into this new #MeToo world bravely and honestly. Only this way can we create a world where everyone is safe. This is the work of our community. It is not the work of an individual alone in therapy who is told too often to forgive, move on, and get over it. I do not know how this can happen without reconciliation. As the victim, I feel powerless. I am too aware that some do not want to hear me call myself a victim nor admit that I feel powerless, but there it is, my truth. I am too worn out to do anymore of this work on my own. Who will the champion be?  It’s Christmas time. Everyone wants a tender story of goodwill. I could share one of those stories with you. I have at least ten. I could tell you how the outpouring of new coats filled my office so that I couldn’t even walk to my closet; we delivered over 60 coats to low income children at the Chittick School. I could tell you about the bags filled with good things for children who have nothing to eat delivered to my house daily. I could tell you about the two brand new bikes in the church parlor waiting to be delivered to children who would otherwise have nothing to open on Christmas day. I could even tell you about the breakfast spread for hard working teachers that folks with no connection to the school made happen because that is what staff at a school deserve. Instead I am going to tell you two stories that might leave you heartbroken, maybe hopeful, and awake to the power of social capital. Story one: Yesterday was food pantry day at Rose’s Bounty at the Stratford Street Church where I am pastor. Running a food pantry is exhausting, complicated, and a bit like managing utter chaos. A little girl was waiting outside with her mother. Wisely, the mother had her daughter wait just inside the door out of the cold. While walking to my office I discovered this sweet child, waiting patiently. She was warmly dressed and quiet. I asked her if her mom was outside. She looked at me with wide eyes. I then asked her if she would like a drink. No response, but an earnest wide-eyed look. I fetched her a juice box and raisins. She responded to my meager gift, “Gracias.” Manners and patience she had in abundance, and only Spanish. But why wasn’t she in school? She was old enough. Our Spanish speaking volunteer and client, Jamie, was the person to help. Before the commotion started, I recruited Jamie to help me speak with the parent so we could enroll this wide eyed child in school. Jamie didn’t forget. In the middle of the chaos, he found the mom and brought her to me, ready to translate. To our surprise, the mother spoke perfect English. How was this possible? In the middle of a hundred plus people shopping for food, I learned her story. She is Venezuelan. She lived in the U.S. for sometime as a child which is why her English was perfect. She returned to Venezuela with her family before high school, but the grinding poverty and political unrest was too much. Fortunately, she was able to escape, and she was able to bring her daughter. Tears rose in her eyes, falling silently as she gripped the pink jacket enfolding her daughter in warmth. The daughter watched as we cried. Her daughter wasn’t in school because she didn’t want to lose her. What if ICE found her in school? What if the teachers reported her? What if she was deported? I have social capital: I am a well educated, rich white woman AND a pastor. Somehow when the poor discover I am a pastor they immediately trust me. I only have to utter the words “I am a minister” and faces relax, language slows, and always there is an exhale. I assured this desperate mom that all children, regardless of their housing situation, citizenship status, or language, can attend school in Boston. Quickly she shared this news with her daughter whose little face lit up. She could go to school. I grabbed that mother’s hands and assured her that her daughter would not be taken from her, that they were safe, that they would survive, and then I cried with her. I’m not sure if I cried from joy or because I knew I wasn’t telling the whole truth. I do believe that in Boston, with the right precautions, you are relatively safe as an undocumented immigrant, especially in the school system. Yet before me was a loving mother who had risked everything to escape grinding poverty in Venezuela, but in America was terrified to send her child to school. What kind of world do we live in? Later today I received a text from the mother, “You have been an angel for my daughter and me that I cannot put into words. Thank you, thank you. Bless you this Christmas.” I am no angel. I am just a privileged woman who knows the federal law: public schools may not ask about a child’s immigration status, Plyler vs. Doe (457 U.S. 202 (1982)). Story two: We had a new client at the food pantry today. She saw we had children’s coats and asked if she could look through them for her son. Of course, we told her. She found me outside later, shoveling the walkway. She wanted to make sure she thanked me for the help. Then she asked, “Do you have another shovel?” I insisted she didn’t need to help me. “Go home and unpack your groceries.” “I feel bad,” she told me. “What for?” I asked. “Because I don’t want you shoveling alone.” I retrieved the other snow shovel. We talked while we shoveled. I found out this tall woman was not only a mom but a college graduate. Where from I asked? Northeastern. She is also an immigrant. She is also the first person in her family to graduate from college. Her career derailed when her young son started having seizures and her young brother died. She had to leave work to care for her son and her depression was overwhelming after her brother’s death. She was homeless for over a year, but she moved into section eight housing in August. Her son is doing so much better since they have been living in permanent housing. Once, she had dreamed of going to law school. Now, she is hopeful that she is back on track. If my son had seizures, my job would give me time off. If I was deeply depressed my family would take care of me, as my in-laws did when they moved in for three weeks while I had postpartum depression. I would never be homeless. I know so many people with extra rooms, extra houses (!), and extra bank accounts. I would be fine. It would be hard, but I would be fine. My life trajectory might be paused, but never derailed. Social Capital: Social Capital is difficult to measure. I know I have a lot, but yesterdayI learned I have even more social capital than I realized. I knew a wide-eyed child could go to school and my life wasn’t derailed by postpartum depression because I am:

Mary and Joseph had very little social capital. They were homeless migrants, and later immigrants when they fled Herod’s violent rule. No relatives in Bethlehem would take them into their homes (remember Bethlehem was Joseph’s hometown). As far as we know they were uneducated peasants. The miracle of Christmas is this: it was to these two people first, and then to all of us, that the Prince of Peace, the Savior, was born. Emmanuel. God with us. Social capital did not enter into God’s Emmanuel equation.

This Christmas, let us remember the story of a child born to parents with no social capital. Let us remember that God first came to them. Today, let us be reassured that God is first with the Venezuelan mother and her daughter and the homeless college graduate and her son. The story of Christmas is not a story of cheap charity. The story of Christmas is the of a God who accompanies those who are the least, the last, the forgotten. If we trust in this God, then social capital can no longer be the yardstick by which we measure an individual’s worth. In God’s eyes, we are all infinitely valuable.  This is not a joke. The following people walk into a coffee shop: A white man, well dressed and handsome. Ivy League educated. A black man in a hoodie. A punked out teenage girl with dreads. A female jewish rabbi with a brush cut. A gorgeous Brazilian woman (This is my stereotype. I’ve yet to meet a Brazilian woman who is not gorgeous). A white teenage girl, nondescript, shy. A white teenage boy, nondescript. A Hispanic teenage boy wearing a football jersey. An imam (Muslim minister), wearing his clerical dress. A six foot-two transgendered woman. A white female minister who is a rabid feminist (yes that’s me). Who is likely to kill everyone in the coffee shop with a gun? Yep, one of the white men. Statistically, when it comes to mass murder in America, white men are disproportionately responsible. You can read proof of this assertion here. Who is most likely to be a sexual assailant? I don’t think I need to even answer that one for you, but just in case you are confused: any man in the coffee shop. Any man could assault any woman. This DOES NOT mean all the men will, or any man will. Yet we cannot ignore that 1 in 3 women in America are sexually assaulted or raped by a man in their lifetime. Who could be sexually assaulted? Any woman in the coffee shop. Any woman. Sexual assault has nothing to do with looks. It has to do with power. Predators often prey upon the “nondescript shy girl” because she seems the least powerful. In addition, the teenage boy could be assaulted due to his less powerful position. Transgender and queer folks report an even higher percentage of sexual assault than straight women. Let that sink in. Who is likely to start a physical fight? The Rabbi and Imam? Nope. In fact, if they are working hard for peace like many religious leaders in this country, they might be really pleased to find themselves in a coffee shop together, the common cup of java between them. After what we saw during Brett Kavanagh’s confirmation hearing, I would venture to guess in this America First Culture that the most likely person to start a fight is the ivy-league-educated, well dressed white man. Especially if he’s had some beer, because he really likes beer. He might become really angry when he discovers he can’t be the first in line, or that his barista doesn’t speak perfect English, or that the man with the hoodie needs to use the bathroom. Who knows, maybe he’ll be really belligerent when he discovers that it’s a coffee house, not a bar, with no beer on tap. Because you know, he really likes beer. And he’ll certainly think it is his prerogative to interrupt and belittle you whenever he gets the chance because he has always been in power. Always. He has no idea there is any other way to act because all of his life everyone has listened, cleared the way, and honored his power. If I were in that coffee shop, I would be most afraid of the white man. Hopefully, in my recent I-am-so-angry state, I wouldn’t pick a fight with him. **** Everything I just wrote is hypothetical. It relies heavily on stereotypes, assumes many things, and places everyone in simplified categories. But it also makes a point, doesn’t it? The “old bulls,” as Dan Rather named them, have been in control from the beginning of this country’s inception. They don’t want to lose their power, so they are spinning alternative realities to match alternative facts that attest they are the ones oppressed. They are not going to give up their power without an epic battle. That’s why, after the Kavanaugh hearings, Republicans reported a spike in contributions. That is also why they are crying wolf. The old bulls are unwilling to look seriously at how power has eaten away at their moral center. Yet some white men are willing to converse, are willing to consider the painful stereotypes I imagined in the coffee shop. But are they truly white men, if they are willing to move beyond their tribal identity and join the rest of our melting pot beauty, where we all enter a coffee shop on equal footing? ****  After Kavanaugh's hearing, it has became apparent to me that the old bulls are unwilling to look critically at their behavior or the way that power and privilege has corrupted their souls. In response, I have developed a new personal strategy: White men can no longer assume my respect; they must earn it. Everytime. Everytime. Imagine if white men had to earn our respect instead of assuming they already have it? Suppose they had to serve their way into responsibility, instead of ruling their way into power? I’m serious. Think about it. What if when that well dressed, Ivy league educated white man walked into the coffee house, he worked hard to win everyone’s respect? What if he was gracious, patient, and engaged with his community around him? What if he gave a large tip to the barista since he makes the most money? (BTW, men do tend to be better tippers than women). What if he let the quiet shy girl cut in front of him? What if he talked about “the game” or even the weather or the coffee with everyone else in line or at tables, especially those folks around him who have been inculturated to feel like his subordinate? What would happen then? **** As a young, female minister, I had to earn the respect of my male colleagues and the congregations I served. This was sometimes unjust and other times appropriate. As a twenty five year old candidate for ordination I had to answer questions my male colleagues didn’t: How do you plan on being a mother and pastor? I also had to endure critiques about my high voice (give me a break) and misplaced guidance about how as a young woman I should really be an associate pastor for families and youth (spare me). I even had to manage my looks: What should I wear on a Sunday morning under that robe? Thank you for your well wishes, but no, you can’t tell me you like my legs(!). This balancing act, always wondering just what I could say and how I could act in a way still authentic to myself, while also winning the approval of those who granted me my authority was exhausting. I am certain my male white colleagues were not under such pressure. Appropriately, as a newly ordained minister, I also had to earn my stripes. This took thoughtful and meaningful attention to my job. With each interaction, I earned my beloved parishioners trust as I visited in hospitals, taught confirmation classes, showed up at fall clean up day, and preached. This earnest attention, although at times exhausting, was also life giving. I was living into my call as a pastor. I misstepped, soared, learned, changed, goofed, and grew. In the end, I earned my stripes, solely because the majority of people I served respected me as their pastor and trusted me as a person. I do not, and will never, take this respect lightly. In fact, it is an abiding blessing that sustains me in my work. Just as I am certain my male colleagues never had to pay attention to their clothes nor answer questions about the pitch of their voice, I am also certain, like me, they had to earn the trust and respect of their congregations. I have a hunch it was easier for them. They wore suits on Sunday. Their voices were naturally deeper. They had potential, whereas I was a wild card. But still, I know my dear male colleagues worked hard to earn their stripes too. I have many “white male” colleagues whom I deeply admire and know for a fact worked hard to shed stereotypes about “male ministers” that often created harmful barriers between themselves and their congregations. **** What if white men, like every young female on the planet, had to earn our respect first instead of stampeding through our common spaces like the old bulls they are? What if they saw themselves not as entitled to power, but instead as one of many called to share in the creation of a just and equal society? What if they had to, like I had to as a young minister, earn the trust and respect of others with whom they shared this country? For this angry female minister, it’s over. You old bulls don’t automatically have my respect any longer. You have to earn it. So start working. And if you don’t care, that’s okay. We will be voting you out. We will stop buying from your companies, because there are more of us than there are of you. You are OLD bulls. A whole new herd is moving in. If you do care, welcome to this beautiful community called America. Because here, in the real America, we, all of us--men, women, white, black, brown, gay, straight, religious, atheist, rich, poor, LGBTQ+, straight, educated or not--together, we are building a democracy.  Before the #metoo movement became defined with a hashtag, I found myself in the throws of an intense sexual abuse investigation. With an open letter to the Board of Trustees at our high school, my childhood friend, Liza, and I forced our alma mater to look deep into its past and its current culture regarding sexual abuse. The incident we brought to their attention occurred over twenty years prior to our letter, but it was as raw to us as when we were 17 year old girl-women. Although I was not the abused, but rather the “defender” of my abused friend, Liza and I share this story intimately. Our roles and experiences are different, but we were both victims of a culture that ignored sexual abuse. The investigation we triggered was simultaneously healing and difficult. You can read the blog I wrote about this almost cliche sexual abuse story of institutional preservation, male power, and female silencing. When the news broke this week about Professor Christine Blasey Ford’s story of survival and courage, my experience confronting my alma mater came crashing back. Each news story, each detailed article incessantly picked at my #metoo wound. I was pleased to discover that my wound is mostly healed, but I could not ignore the connections. I could not ignore the anger that rose from deep within. I also could not ignore how defeated I felt. How many times will I have to listen to commentators ask, “Why is she telling her story now?” or “It happened 30 years ago. How can she be sure?” Let me offer “you” some answers, “you” being the emotionally-bankrupt-head-in-the-sand politicians who ask such ignorant questions! Or as the Hawaii Sen Mazie Hirono said, “Shut up and Step Up!” But in my case I want you to Shut Up and Listen Up. Professor Ford is confronting a country. I only confronted a school. Imagine her courage. She has nothing to gain! Nor did I. Why is she telling her story now? Um, isn’t that obvious? Because Brett Kavanaugh has been nominated to the Supreme Court. Professor Ford is a patriot for sacrificing her privacy for the good of our country. If you need a more nuanced answer: Christine Blasely Ford did tell her story earlier to her husband, therapist and probably many others. Women have been telling our stories of sexual abuse for centuries, but we have been silenced. For many of us our silencing has been covert. We’ve been silenced by our culture everytime we hear, “Boys will be boys” or my personal favorite, “It was just locker room talk.” We’ve been silenced when our mothers told us never to find ourselves in a room alone with a boy, because whatever happens after would be our fault. We’ve been silenced by our fellow classmates who heard the rumors about what happened and lowered their heads in shame, unable to look at us . . . as if we were at fault. We’ve been silenced by every comment that insinuates the way we dress, the way we act, the way we look, “asks for it.” We have been silenced by our sexual partners who didn’t want the past to inconveniently interrupt their pleasure. I am confident that Professor Ford told a handful of people her story about the bathing suit that saved her. In fact, I am positive everytime she found herself struggling to take off a one piece bathing suit in a bathroom stall, she murmured a silent thanks. I can imagine the telling of her story, piece by piece, that has moved her from a place of shame and fear to a new place of survival and healing. She has told her story. Now she is telling it again. We have all told our stories before. YOU HAVEN’T LISTENED. I told my my headmaster twice that my friend was being abused by a teacher. He didn’t listen and worse, he didn’t care. I then told my dean and she told me to be quiet. Her words, “Abby, we already know what you think. Be quiet!” echo in my psyche. Stop asking why we’ve never spoken up before. We have. You haven’t listened. And just to be clear, we get to share our stories of abuse and survival whenever we want. They belong to us. Not you. How can she be sure what happened 30 years ago? Scientists have proven that traumatic experiences leave a signature in the brain that is hard to erase. I can attest to this truth. I can tell you where all my classrooms were located in my high school, my teachers’ names, and more. I have a very good memory. I could not tell you, however, the color of the walls, where each teacher placed book shelves or desks. I could only guess. But I can tell you every detail of my dean’s office. I can tell you every detail of the meeting, where a group of other students and I went to seek help for our classmate who was being abused. I can tell you where I sat in that small room and where the dean first sat, and then stood, leaning against her desk. I can remember the hesitant, almost stalling voices of my classmates, too afraid to say the word, “sex.” I know now that my memory is so clear because the experience was traumatic. I’ve carried this moment with me for years in technicolor, and I can hear my dean’s voice, “Abby, we already know what you think. Be quiet!” I am not surprised that Professor Ford can remember the sequence of events during that particular high school party: the two drunks boys pushing her into a deserted room, the struggle, the bathing suit, the hand over her mouth, the tumble, and her escape. Years do not erase the memory of trauma. If only they did. When such memories are buried by the psyche so the victim can survive, they always return to haunt their hosts. In my work as a pastor I can’t tell you the number of times I have borne witness to women in the throws of terrible depressions who discover they have buried memories of sexual abuse. I have seen the scars on teenage girls’ arms after they have cut themselves because it was the only way they could dull the repressed memory-pain of sexual abuse. I have listened to a 60 year old woman tell of her father’s daily rape that she had blocked from her memory until she finally felt safe after his death. Professor Ford has a story to tell. She remembers this story too vividly. Sexual abuse will never stop until we listen and believe. She is telling this story again with clarity and courage because it matters to the future of our country. It also matters to the many women who are still hiding their #metoo stories. Telling and listening is the only way as a nation we can heal and move forward into a new way of living as sexual beings of all gendered identities who never accept abuse as the norm. #MeToo #UsToo #AllofUs |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed