I'll be going live on Facebook.

I've started a Podcast...

The Progressive Sacred. Authentic conversations about Christianity we all want to have, but are afraid to begin.

Have you ever gotten a look in Bible study when you bring up an alternative interpretation of the text? Have you ever left a church because their view of christianity was too rigid, but miss practicing your faith? Have you ever secretly identified as Christian but are positive you have nothing in common with 90% of the Christian faith presented in the media? If so, this Podcast is for you. Each episode is a fearless conversation about a difficult topic in the Christian church and in our larger culture.

Have you ever gotten a look in Bible study when you bring up an alternative interpretation of the text? Have you ever left a church because their view of christianity was too rigid, but miss practicing your faith? Have you ever secretly identified as Christian but are positive you have nothing in common with 90% of the Christian faith presented in the media? If so, this Podcast is for you. Each episode is a fearless conversation about a difficult topic in the Christian church and in our larger culture.

THE PTJ Crew. Meet the three people who make up the PTJ Crew. That would be the Preacher (Abby), and Theologian (Jon Paul Sydnor) and a guy named Julio. Someone how these three folks (two through marriage) have decided that working on a podcast together is exactly what they need to be doing. But how and why is something more complicated to explain. Listen to Podcast #0 to learn a bit more behind the origin of this crew and the development of the Progressive Sacred.

Spoiler Alert:

A Preacher, a theologian, and a guy named Julio walk into a bar…

Spoiler Alert:

A Preacher, a theologian, and a guy named Julio walk into a bar…

Abby's Latest Blogs

Maybe Love is Irrational, but I believe in the Resurrection hook, line, and sinker

I am a rational person who embraces science and I believe in the resurrection.

Let’s start again. I AM a rational person. I can hear my husband laughing right now as I type these words, because he’s seen me lose my cool once or twice. Ignore his laughter; I am rational! Example: when I worry about my kids contracting some horrible childhood illness, I look up the statistical likelihood of someone actually getting that illness. Then, I embrace the rational numbers and move on with my day.

When it comes to my faith, I also tend to be level headed. I don’t get hung up on virgin births or single miracle stories. Jesus walking on water? Powerful metaphor, but I am not concerned if it happened or not. I’m the first person to admit I think the Bible is riddled with mistakes and even some blatant mistruths. There are no biblical handbooks with statistics to reference there are for childhood illnesses, but I try to embrace the large sweep of love present in the Bible as my rational guide to faith.

And I believe in the resurrection. In fact, I believe in the resurrection hook, line, and sinker. Literally. From a 21st century scientific perspective this is utterly irrational. Perhaps this is just faith. Perhaps this is just hopeful thinking. I’m not sure. But there it is. The belief that Jesus was dead and three days later walked out of the grave, appeared to the women, stuck out his bloody hands to Thomas to reassure him, and then ate fish beside the sea shore with the other disciples who had fled and gone back to business as usual. Yes, I believe it all.

A faithful companion along the journey commented: “Sorry, Abby, I can’t worship a zombie.” I respect that and even find the comment comically accurate. So why do I believe in the resurrection? I don’t have an answer. At least not a good answer. I can only offer the following:

I believe in God and for this reason, I believe in hope, even when realistic people tell me to be hopeless. I gave up believing that God could single-handedly rescue starving orphans, Haitians from earthquakes, mothers with debilitating depression, victims of violence, struggling families, or trauma survivors tormented by nightmares. So if I believe in a powerless God and every day I encounter the utter brokenness of this world, then what’s the point? I am left with no choice than to believe in a God who does something!

I believe in a God who loves.

I believe in a God whose love is more powerful, more healing, and more creative than anything we broken humans can imagine.

I believe in a God who invites us into a dance of co-creating love.

I believe in a God whose love is active in this world through this dance of co-creation.

I believe in a God who grants hope to the hopeless. Real hope.

What does this have to do with the resurrection? The resurrection is the ultimate expression of God’s co-creating love.

God did not possess the sort of military power that could defeat the systematically violent Roman Empire. Hence Jesus died a brutal death on the cross. But God did possess the power of co-creating love that sprang Jesus from the grave. Together, Jesus and God defeated suffering and death with this co-creating love. The resurrection, the defeat of the grave, continues to offer today the final word: Love!

This final word gives me hope for the starving orphan, the depressed parent, the individual facing PTSD after a childhood filled with violence, the cancer patient, the Palestinian and Israeli leaders trying to rebuild their communities in peace. The resurrection calls me to dance with love on my darkest days, when I am sure there is only suffering to be found. The resurrection calls me to co-create in this world, instead of sitting and weeping. The resurrection calls me to roll up my sleeves, to pull out my checkbook, to fall to my knees, to utter a prayer, to hold on. The resurrection is God’s final proof that love is more powerful than anything else, even evil, even death.

I know that what I believe can be questioned. Pure rationalists can poke holes in my truth. I don’t care. It’s what I believe. It’s the faith of one broken disciple, a 21st century pastor following Jesus, placing one foot in front of the other on the journey, and feeling powerlessness yield to an even greater power—love.

Let’s start again. I AM a rational person. I can hear my husband laughing right now as I type these words, because he’s seen me lose my cool once or twice. Ignore his laughter; I am rational! Example: when I worry about my kids contracting some horrible childhood illness, I look up the statistical likelihood of someone actually getting that illness. Then, I embrace the rational numbers and move on with my day.

When it comes to my faith, I also tend to be level headed. I don’t get hung up on virgin births or single miracle stories. Jesus walking on water? Powerful metaphor, but I am not concerned if it happened or not. I’m the first person to admit I think the Bible is riddled with mistakes and even some blatant mistruths. There are no biblical handbooks with statistics to reference there are for childhood illnesses, but I try to embrace the large sweep of love present in the Bible as my rational guide to faith.

And I believe in the resurrection. In fact, I believe in the resurrection hook, line, and sinker. Literally. From a 21st century scientific perspective this is utterly irrational. Perhaps this is just faith. Perhaps this is just hopeful thinking. I’m not sure. But there it is. The belief that Jesus was dead and three days later walked out of the grave, appeared to the women, stuck out his bloody hands to Thomas to reassure him, and then ate fish beside the sea shore with the other disciples who had fled and gone back to business as usual. Yes, I believe it all.

A faithful companion along the journey commented: “Sorry, Abby, I can’t worship a zombie.” I respect that and even find the comment comically accurate. So why do I believe in the resurrection? I don’t have an answer. At least not a good answer. I can only offer the following:

I believe in God and for this reason, I believe in hope, even when realistic people tell me to be hopeless. I gave up believing that God could single-handedly rescue starving orphans, Haitians from earthquakes, mothers with debilitating depression, victims of violence, struggling families, or trauma survivors tormented by nightmares. So if I believe in a powerless God and every day I encounter the utter brokenness of this world, then what’s the point? I am left with no choice than to believe in a God who does something!

I believe in a God who loves.

I believe in a God whose love is more powerful, more healing, and more creative than anything we broken humans can imagine.

I believe in a God who invites us into a dance of co-creating love.

I believe in a God whose love is active in this world through this dance of co-creation.

I believe in a God who grants hope to the hopeless. Real hope.

What does this have to do with the resurrection? The resurrection is the ultimate expression of God’s co-creating love.

God did not possess the sort of military power that could defeat the systematically violent Roman Empire. Hence Jesus died a brutal death on the cross. But God did possess the power of co-creating love that sprang Jesus from the grave. Together, Jesus and God defeated suffering and death with this co-creating love. The resurrection, the defeat of the grave, continues to offer today the final word: Love!

This final word gives me hope for the starving orphan, the depressed parent, the individual facing PTSD after a childhood filled with violence, the cancer patient, the Palestinian and Israeli leaders trying to rebuild their communities in peace. The resurrection calls me to dance with love on my darkest days, when I am sure there is only suffering to be found. The resurrection calls me to co-create in this world, instead of sitting and weeping. The resurrection calls me to roll up my sleeves, to pull out my checkbook, to fall to my knees, to utter a prayer, to hold on. The resurrection is God’s final proof that love is more powerful than anything else, even evil, even death.

I know that what I believe can be questioned. Pure rationalists can poke holes in my truth. I don’t care. It’s what I believe. It’s the faith of one broken disciple, a 21st century pastor following Jesus, placing one foot in front of the other on the journey, and feeling powerlessness yield to an even greater power—love.

The Violence of the Cross is NOT Sacred and it shouldn't be taught to children as such!

There’s nothing like a bloody, anguished Jesus to ruin your religious experience as a child. Did I just say that out loud? Yes I did. If you need to read the above sentence again, please do.

On the cusp of Bad Friday (you might refer to it as Good Friday, but no day a human dies on a cross should be remembered as a good day), I would like to share a very powerful and haunting story from a childhood trauma survivor. This survivor describes their parent as a monster. As a child, they remember peering at the wretched crucifix in their church, Sunday after Sunday. They remember vividly kneeling beneath Jesus’ bloodied body and asking, why would they let this happen to you? Soon the violence of their home was mirrored each Sunday in church as they peered up at the crucifix hanging above the altar. As an adult, even after years of therapy, they have been unable to separate the domestic violence they survived from the vision of Jesus crucified.

Imagine the imprint the crucifixion has on young minds. If our salvation comes from Jesus’s crucifixion, then the crucifix teaches children that violence is good. Worse, it teaches them that violence is sacred. For two millennia, the church has blessed violence and elevated it to the sacred. And we have exposed generations of children to this unholy endorsement of unholy violence.

Christianity is so often associated with wholesomeness and a sanitary innocence. Children raised in “Christian homes” would never watch an R-rated movie. Instead, they are introduced to clean images of faith: pristine children running through sunny fields to attend church, happy families praying before bed, and all problems neatly resolved at the end of the movie.

It’s a bit ironic, isn’t it? Such sanitary images of Jesus and wholesome images of living--- in a faith tradition that divinizes violence. Do you disagree? If you are adamant that the church does not divinize violence, can you please explain why churches are filled with 14 different venerations of the cross that depict every step of the horrifying crucifixion?

The worship of the cross idolizes violence.

I have a friend who wears a “lethal injection Jesus” instead of a cross around her neck. Yes, you read that correctly. She refuses to pretend the cross is sacred. By offering an alternative image of Jesus' death, not by crucifixion but by lethal injection, this alarming necklace states the truth: Jesus died by state sponsored execution. There is nothing sacred, nothing holy, nothing acceptable about such a violent death.

Then how are we to mark this significant day in the Holy Week story? Simply with the truth. Jesus died a terrible death at the hands of unjust power. That death cannot and should not be venerated as holy. It should be remembered for what it was: horrifyingly cruel. Recognizing the truth of the crucifixion makes God’s resurrecting and transformative love on Easter morn even more powerful.

What should we do with our children on Bad Friday? First, please don’t tell them that a loving prophet was tortured to death to save us from our sins. Second, without question, throw out all of the bloody images of Jesus please! Yes! I would rather destroy thousands of crucifixes than have one more child learn from an early age that violence is sacred. I would also encourage families and religious leaders/educators to teach children the entire story of Holy Week. When it is time to teach children about Friday, name the horror of the cross, making sure children understand that Jesus’ death was awful and wrong. Tell them that God had a different idea about power; that God used God’s power for love. This love is the answer to the violence of the cross, and this love is infinitely more powerful than the cross.

That’s where we will find our healing---not in the violence of the cross, but in the miracle of the resurrection; not in useless suffering, but in creative hope; not in the power of empire, but in a community of love. We cannot celebrate the death of an innocent, beautiful man, but we can celebrate God’s victory over the machinations of evil. Please join me in changing the way we tell the story this Friday.

There’s nothing like a bloody, anguished Jesus to ruin your religious experience as a child. Did I just say that out loud? Yes I did. If you need to read the above sentence again, please do.

On the cusp of Bad Friday (you might refer to it as Good Friday, but no day a human dies on a cross should be remembered as a good day), I would like to share a very powerful and haunting story from a childhood trauma survivor. This survivor describes their parent as a monster. As a child, they remember peering at the wretched crucifix in their church, Sunday after Sunday. They remember vividly kneeling beneath Jesus’ bloodied body and asking, why would they let this happen to you? Soon the violence of their home was mirrored each Sunday in church as they peered up at the crucifix hanging above the altar. As an adult, even after years of therapy, they have been unable to separate the domestic violence they survived from the vision of Jesus crucified.

Imagine the imprint the crucifixion has on young minds. If our salvation comes from Jesus’s crucifixion, then the crucifix teaches children that violence is good. Worse, it teaches them that violence is sacred. For two millennia, the church has blessed violence and elevated it to the sacred. And we have exposed generations of children to this unholy endorsement of unholy violence.

Christianity is so often associated with wholesomeness and a sanitary innocence. Children raised in “Christian homes” would never watch an R-rated movie. Instead, they are introduced to clean images of faith: pristine children running through sunny fields to attend church, happy families praying before bed, and all problems neatly resolved at the end of the movie.

It’s a bit ironic, isn’t it? Such sanitary images of Jesus and wholesome images of living--- in a faith tradition that divinizes violence. Do you disagree? If you are adamant that the church does not divinize violence, can you please explain why churches are filled with 14 different venerations of the cross that depict every step of the horrifying crucifixion?

The worship of the cross idolizes violence.

I have a friend who wears a “lethal injection Jesus” instead of a cross around her neck. Yes, you read that correctly. She refuses to pretend the cross is sacred. By offering an alternative image of Jesus' death, not by crucifixion but by lethal injection, this alarming necklace states the truth: Jesus died by state sponsored execution. There is nothing sacred, nothing holy, nothing acceptable about such a violent death.

Then how are we to mark this significant day in the Holy Week story? Simply with the truth. Jesus died a terrible death at the hands of unjust power. That death cannot and should not be venerated as holy. It should be remembered for what it was: horrifyingly cruel. Recognizing the truth of the crucifixion makes God’s resurrecting and transformative love on Easter morn even more powerful.

What should we do with our children on Bad Friday? First, please don’t tell them that a loving prophet was tortured to death to save us from our sins. Second, without question, throw out all of the bloody images of Jesus please! Yes! I would rather destroy thousands of crucifixes than have one more child learn from an early age that violence is sacred. I would also encourage families and religious leaders/educators to teach children the entire story of Holy Week. When it is time to teach children about Friday, name the horror of the cross, making sure children understand that Jesus’ death was awful and wrong. Tell them that God had a different idea about power; that God used God’s power for love. This love is the answer to the violence of the cross, and this love is infinitely more powerful than the cross.

That’s where we will find our healing---not in the violence of the cross, but in the miracle of the resurrection; not in useless suffering, but in creative hope; not in the power of empire, but in a community of love. We cannot celebrate the death of an innocent, beautiful man, but we can celebrate God’s victory over the machinations of evil. Please join me in changing the way we tell the story this Friday.

I wrote the below blog 10 years ago for Mother's Day. On this complicated holiday, that I vehemently despise since I find it to be exclusionary, heteronormative, and sneakily misogynistic, I wanted to honor my own journey to motherhood. I also wanted to honor the reality that rarely is the road to parenthood simple. In fact, I have discovered over these past ten years that NOTHING about parenthood is simple. 10 years later I find myself struggling with new complications: How do you raises teenagers who want less emotional connection, but still need it? (If you have a answer, please let me know.) How do you honor your children's autonomy? Why do I enjoy loving my two year old goddaughter more than teenagers? Should I feel guilty about this? I have no insightful blog about these latest questions, but beow in my honest story.

JOURNEY TO MOTHERHOOD, written May 2012

The vast majority of my sexual education focused on how to keep from getting pregnant, so much so that I naively assumed that to get pregnant you need only to have unprotected sex once. Without revealing any embarrassing details, my husband and I truly thought I would be pregnant in a month’s time the summer after I received my graduate degree. We calculated on our hands more than once that our baby would be arriving sometime in March. But my period came after that first month of trying; I cried and immediately alleged that there was something wrong in our technique. Then the next period came; I sobbed and assured my husband with my typical dramatic flair that I was ready to adopt.

After two missed attempts, getting pregnant became something to accomplish. The process was not to be enjoyed. I peed on sticks, prayed, raised my feet over my head, talked to every recently pregnant woman I could find, and waited in fear. So it was with great joy and relief that after six months of trying I discovered I was pregnant the second week of my very first pastorate. We glowed with anticipation and again naively assumed that everything would be smooth sailing—we were pregnant now. All we had to do was wait nine months for the arrival of our baby.

A week before my ordination, while being questioned on the floor of presbytery, I knew I was miscarrying at ten weeks. The sight of blood before the presbytery meeting lead to a call to my midwives, yet I knew I could not miss that night’s meeting. My ordination depended on it. I stood before a group of elders and pastors who asked me highly controversial theological questions about my position on atonement and salvation, but I remember only thinking about where I could find a bathroom after so I could check if there was more blood spotting my underwear. The next day an ultrasound stole the promise of that sweet child from us. Our final innocence, as those who deeply yearned for children of our own, was over. Fear laced our life as parents from then on.

I have never forgotten our first baby, long forgotten by the world, nor the sheer uncomplicated joy accompanying the promise of that first positive pregnancy test. Almost eleven years later, I cannot bring myself to throw away the medical records that document my miscarriage; they are my only physical reminder of our first child.

Our first remains unnamed. I am not sure why we have been unable to name our child. Perhaps because it still feels like a dream, the medical records the only thing confirming that it did really happen. Or perhaps because we never had a strong sense whether our promised child was a boy or girl. Yet still, this child’s brief life has embedded itself deep into the fabric of our life together as parents.

****

Silent waiting ruled our lives in our four bedroom parsonage. We couldn’t bear to wait, yet we had no other alternative. Again we found ourselves consumed by the process of getting pregnant. Each month our waiting was laced with hope, but every period plunged us back into sorrow and mourning and despair. After dinner, with no children to tend to, with only work awaiting us, we would fill up the empty waiting with an ongoing game of gin rummy. We kept our grief and loneliness at bay by staying in constant motion. Then we got a dog. We needed something to love. And then the testing began—painful dyes injected into tubes, brown paper bags and dirty magazines, and results.

At twenty-six years of age I began IVF—in vitro fertilization. There were waiting rooms filled with silent women, waiting for blood work, waiting for consults with specialists in white coats, and waiting for the defining test result. Occasionally a stricken partner waited alongside us. There were needles and vials upon vials of hormones, delivered efficiently by Federal Express. There were the evenings my husband’s face, gripped with steely resolution, stuck a needle deep into my hip, I would sob in pain, only to run off to a deacons’ meeting after a band-aid was applied. We waited in silence, hoping, fearing the worst, and preparing for the unthinkable, another round of shots and harvesting and waiting.

But it worked. At five weeks gestation we saw the fluttering heart of our baby. Still we were forced to wait. We could not embrace the promise of that undulating muscle until the crucial marker of thirteen weeks. We had been deceived before. Thankfully, with time that tiny beating heart grew into the strong heart of a screaming ten pound baby boy.

I wish my painful story of conception and gestation ended here, but the joy of pregnancy has eluded me. My third pregnancy ended in miscarriage at thirteen weeks on Ash Wednesday, after announcing to my entire congregation the Sunday prior that I was pregnant. This time we named our baby—Kasia. On a warm Spring day we planted summer bulbs in her memory, our young son wading in the water nearby.

I spent my fourth pregnancy reeling in terror, holding my breath between each revealing gesture of my baby’s limbs within the womb, sure that the baby, even at twenty weeks, would die before I had a chance to hold it. This pregnancy, which produced another ten pound baby boy, is mostly lost to me. I can only remember the terror. I am not sure if I ever experienced any joy until my second son was six weeks old, nursing calmly and happily at my breast.

****

No one ever told me how difficult it would be. No one—not my mother, or my aunts, or my grandmothers, or the women whose children I cared for, no one. After I lost my third child, I awoke in the middle of the night, unable to breathe, a crushing weight on my chest, and the clear resolution that I could never have another child. I was certain in that still dark room that the pain of pregnancy would keep me—the teenager who watched a family of five and did their dishes without breaking a sweat, the college student who babysat every Friday night instead of going out, the young bride who had decided with her beloved mate that they would raise four children together—from ever having more than one child. The fear of conception and gestation suffocated all my confidence and all my hope.

I remember one evening in particular, after our first child was born: I hid away in our bedroom and wept. I was utterly exhausted by my dashed hopes and terrified by the chance of more loss. I thought if I wept alone I could ironically protect myself, as if in hiding my fear, no one, including myself would know how really bad it was. I understand now, that I was in essence rejecting the very vulnerability that parenthood entails.

Yet I did not grieve alone; I grieved in the presence of loving community. Grace encircled me with the stories of many gentle people, mostly women, but also men, who had lost children as well. Their stories were ones of pain and grief, but also of hope, survival, and sometimes children. They were the stories of twelve-week-old twin girls, a twenty-five- week old baby girl still referred to as an angel by her parents, a still birth boy, a still birth first, another set of twins, five miscarriages in a row before a healthy baby was born. These stories I laid beside mine. As I entangled my own grief, I came to understand that these stories were the unavoidable stories of conception, gestation, and birth. They are the stories of parenthood.

*****

Sadly, my story continues. After my second son was two I miscarried for a third time. I was placed in the high-risk pregnancy category. They even performed an autopsy of sorts on our sweet 13 week in utero baby girl who we named Elise. I began a regiment of antidepressants and weekly therapy because I could no longer fight the grief and fear on my own. The good news is that somehow, my call to motherhood was so undeniable, I found enough courage to try again. The trying was fraught with waiting and wondering if we would ever get pregnant again. And when finally I did get pregnant, my anxiety spiked and my antidepressant prescription increased from 50 grams to 100 grams. At the end of that successful nine month gestation, I had a perfectly healthy baby girl. And three days later I was greeted with debilitating postpartum depression.

I do not want to make light of postpartum depression; it was horrible. Yet I was fortunate that I received medical help immediately and responded positively to medication. For me, more than anything, postpartum seemed like a slap in the face after the exhausting effort I had put forward to have a third child. I remember very little of my daughter’s first six months of life. Now that she is three this seems to bother me less. Who remembers the blur of sleepless nursing anyhow?

****

My children are older now; their bodies stretch out, filling their beds, relaxed in sleep. Some days I barely remember how painfully I yearned for their presence. Some days I even desire a break from all the work that they generate —lunch boxes, laundry, speech therapy appointments, lacrosse games, snit fits, dishes.

Every mother’s day, I remember with clarity what it was like to yearn desperately to be a mother. Every mother’s day I relish the homemade gifts and earnest attempts at breakfast in bed. And every mother’s day I remember there are many women who feel locked out of the “club” as I smell my children’s hair as they climb into bed with me.

****

I have not one profound thing to say—not one thing that will make sense of any of this pain or longing or unfairness. Some of us end up as mothers, others wait, others mothers more children than ever desired, and still others long for someone with whom to share motherhood.

I pray for all and carry each woman in my heart.

JOURNEY TO MOTHERHOOD, written May 2012

The vast majority of my sexual education focused on how to keep from getting pregnant, so much so that I naively assumed that to get pregnant you need only to have unprotected sex once. Without revealing any embarrassing details, my husband and I truly thought I would be pregnant in a month’s time the summer after I received my graduate degree. We calculated on our hands more than once that our baby would be arriving sometime in March. But my period came after that first month of trying; I cried and immediately alleged that there was something wrong in our technique. Then the next period came; I sobbed and assured my husband with my typical dramatic flair that I was ready to adopt.

After two missed attempts, getting pregnant became something to accomplish. The process was not to be enjoyed. I peed on sticks, prayed, raised my feet over my head, talked to every recently pregnant woman I could find, and waited in fear. So it was with great joy and relief that after six months of trying I discovered I was pregnant the second week of my very first pastorate. We glowed with anticipation and again naively assumed that everything would be smooth sailing—we were pregnant now. All we had to do was wait nine months for the arrival of our baby.

A week before my ordination, while being questioned on the floor of presbytery, I knew I was miscarrying at ten weeks. The sight of blood before the presbytery meeting lead to a call to my midwives, yet I knew I could not miss that night’s meeting. My ordination depended on it. I stood before a group of elders and pastors who asked me highly controversial theological questions about my position on atonement and salvation, but I remember only thinking about where I could find a bathroom after so I could check if there was more blood spotting my underwear. The next day an ultrasound stole the promise of that sweet child from us. Our final innocence, as those who deeply yearned for children of our own, was over. Fear laced our life as parents from then on.

I have never forgotten our first baby, long forgotten by the world, nor the sheer uncomplicated joy accompanying the promise of that first positive pregnancy test. Almost eleven years later, I cannot bring myself to throw away the medical records that document my miscarriage; they are my only physical reminder of our first child.

Our first remains unnamed. I am not sure why we have been unable to name our child. Perhaps because it still feels like a dream, the medical records the only thing confirming that it did really happen. Or perhaps because we never had a strong sense whether our promised child was a boy or girl. Yet still, this child’s brief life has embedded itself deep into the fabric of our life together as parents.

****

Silent waiting ruled our lives in our four bedroom parsonage. We couldn’t bear to wait, yet we had no other alternative. Again we found ourselves consumed by the process of getting pregnant. Each month our waiting was laced with hope, but every period plunged us back into sorrow and mourning and despair. After dinner, with no children to tend to, with only work awaiting us, we would fill up the empty waiting with an ongoing game of gin rummy. We kept our grief and loneliness at bay by staying in constant motion. Then we got a dog. We needed something to love. And then the testing began—painful dyes injected into tubes, brown paper bags and dirty magazines, and results.

At twenty-six years of age I began IVF—in vitro fertilization. There were waiting rooms filled with silent women, waiting for blood work, waiting for consults with specialists in white coats, and waiting for the defining test result. Occasionally a stricken partner waited alongside us. There were needles and vials upon vials of hormones, delivered efficiently by Federal Express. There were the evenings my husband’s face, gripped with steely resolution, stuck a needle deep into my hip, I would sob in pain, only to run off to a deacons’ meeting after a band-aid was applied. We waited in silence, hoping, fearing the worst, and preparing for the unthinkable, another round of shots and harvesting and waiting.

But it worked. At five weeks gestation we saw the fluttering heart of our baby. Still we were forced to wait. We could not embrace the promise of that undulating muscle until the crucial marker of thirteen weeks. We had been deceived before. Thankfully, with time that tiny beating heart grew into the strong heart of a screaming ten pound baby boy.

I wish my painful story of conception and gestation ended here, but the joy of pregnancy has eluded me. My third pregnancy ended in miscarriage at thirteen weeks on Ash Wednesday, after announcing to my entire congregation the Sunday prior that I was pregnant. This time we named our baby—Kasia. On a warm Spring day we planted summer bulbs in her memory, our young son wading in the water nearby.

I spent my fourth pregnancy reeling in terror, holding my breath between each revealing gesture of my baby’s limbs within the womb, sure that the baby, even at twenty weeks, would die before I had a chance to hold it. This pregnancy, which produced another ten pound baby boy, is mostly lost to me. I can only remember the terror. I am not sure if I ever experienced any joy until my second son was six weeks old, nursing calmly and happily at my breast.

****

No one ever told me how difficult it would be. No one—not my mother, or my aunts, or my grandmothers, or the women whose children I cared for, no one. After I lost my third child, I awoke in the middle of the night, unable to breathe, a crushing weight on my chest, and the clear resolution that I could never have another child. I was certain in that still dark room that the pain of pregnancy would keep me—the teenager who watched a family of five and did their dishes without breaking a sweat, the college student who babysat every Friday night instead of going out, the young bride who had decided with her beloved mate that they would raise four children together—from ever having more than one child. The fear of conception and gestation suffocated all my confidence and all my hope.

I remember one evening in particular, after our first child was born: I hid away in our bedroom and wept. I was utterly exhausted by my dashed hopes and terrified by the chance of more loss. I thought if I wept alone I could ironically protect myself, as if in hiding my fear, no one, including myself would know how really bad it was. I understand now, that I was in essence rejecting the very vulnerability that parenthood entails.

Yet I did not grieve alone; I grieved in the presence of loving community. Grace encircled me with the stories of many gentle people, mostly women, but also men, who had lost children as well. Their stories were ones of pain and grief, but also of hope, survival, and sometimes children. They were the stories of twelve-week-old twin girls, a twenty-five- week old baby girl still referred to as an angel by her parents, a still birth boy, a still birth first, another set of twins, five miscarriages in a row before a healthy baby was born. These stories I laid beside mine. As I entangled my own grief, I came to understand that these stories were the unavoidable stories of conception, gestation, and birth. They are the stories of parenthood.

*****

Sadly, my story continues. After my second son was two I miscarried for a third time. I was placed in the high-risk pregnancy category. They even performed an autopsy of sorts on our sweet 13 week in utero baby girl who we named Elise. I began a regiment of antidepressants and weekly therapy because I could no longer fight the grief and fear on my own. The good news is that somehow, my call to motherhood was so undeniable, I found enough courage to try again. The trying was fraught with waiting and wondering if we would ever get pregnant again. And when finally I did get pregnant, my anxiety spiked and my antidepressant prescription increased from 50 grams to 100 grams. At the end of that successful nine month gestation, I had a perfectly healthy baby girl. And three days later I was greeted with debilitating postpartum depression.

I do not want to make light of postpartum depression; it was horrible. Yet I was fortunate that I received medical help immediately and responded positively to medication. For me, more than anything, postpartum seemed like a slap in the face after the exhausting effort I had put forward to have a third child. I remember very little of my daughter’s first six months of life. Now that she is three this seems to bother me less. Who remembers the blur of sleepless nursing anyhow?

****

My children are older now; their bodies stretch out, filling their beds, relaxed in sleep. Some days I barely remember how painfully I yearned for their presence. Some days I even desire a break from all the work that they generate —lunch boxes, laundry, speech therapy appointments, lacrosse games, snit fits, dishes.

Every mother’s day, I remember with clarity what it was like to yearn desperately to be a mother. Every mother’s day I relish the homemade gifts and earnest attempts at breakfast in bed. And every mother’s day I remember there are many women who feel locked out of the “club” as I smell my children’s hair as they climb into bed with me.

****

I have not one profound thing to say—not one thing that will make sense of any of this pain or longing or unfairness. Some of us end up as mothers, others wait, others mothers more children than ever desired, and still others long for someone with whom to share motherhood.

I pray for all and carry each woman in my heart.

The Human Story

I have been shaped by the human story. My book shelves are stacked with autobiographies. My dining room hutch is adorned with teapots and dishes owned by women who have loved me and are now gone. As a pastor, people share with me their deepest stories. I am forever shaped by these encounters.

I have looked for God within the beautiful and terrible, mundane and miraculous, human story. For this reason, I have never read the Bible seeking rules, treating its words as a prescription for how to live. Instead, like a forensic scientist of relationship, I have examined the Bible’s account of individuals and communities for what it means to be human and live fully. I have savored each glimpse into a biblical story that reveals how human love transforms, hate cripples, and desperation guts. I have read and studied all in hopes that I might discover how to live in relationship with God.

Brittany Packnett Cunningham wrote in Time magazine after John Lewis’ death: “Our elders become our ancestors ... What kind of ancestors will we be? Daily, the sum of our future ancestry is being totaled. Will we choose mere words? Or, as Lewis compatriot and fellow hero the Rev. C.T. Vivian reminds us, will it be ‘in that action that we find out who we are’?”

Cunningham’s words have been a burr in my mind: elders, ancestors, futures, words, action. I have wrapped my life in the stories of others-- those I know and those I do not, those who are famous, infamous, and unknown. Their stories peek out at me from a bookshelf, call to me from verses, and even speak to me as I pour tea from a well used tea pot. Yet I have never considered how in this very moment, I am shaping the story that one day I will pass onto the next generation. I have never imagined that I am my very own story and that my story will impact the living and loving of those who follow me.

In these disorienting times it is difficult to know just how to live our story. How shall we not just post about justice, but act for justice, as C.T. Vivian urges? How will I live as a faithful disciple in a world that has branded Christianity as exclusive? How can I enact inclusive Christianity, and not just think it? My questions have led me back to the same spiritual practice: studying the human story as a road map forward. Every day I am learning how to be a better ancestor, because I am surrounded by my own saints-as-ancestors, and I live in their stories.

We can do the work we are called to do because others before us, like John Lewis, and the less famous Mr. White and Kay, have tilled the soil. For this reason, I will share with you during the coming months snippets of human stories that have shaped me, from famous leaders like John Lewis to unknown saints like Mr. White and Kay, from self-proclaimed Christians to those of other faiths--and those who were unsure of their faith. My hope is that these stories will inspire us to continue the larger human story of progress: of a society that ultimately bends toward a God of love and justice . . . even now, or especially now.

*Please look to "Spirit" tab for the continuation of this blog.

I have looked for God within the beautiful and terrible, mundane and miraculous, human story. For this reason, I have never read the Bible seeking rules, treating its words as a prescription for how to live. Instead, like a forensic scientist of relationship, I have examined the Bible’s account of individuals and communities for what it means to be human and live fully. I have savored each glimpse into a biblical story that reveals how human love transforms, hate cripples, and desperation guts. I have read and studied all in hopes that I might discover how to live in relationship with God.

Brittany Packnett Cunningham wrote in Time magazine after John Lewis’ death: “Our elders become our ancestors ... What kind of ancestors will we be? Daily, the sum of our future ancestry is being totaled. Will we choose mere words? Or, as Lewis compatriot and fellow hero the Rev. C.T. Vivian reminds us, will it be ‘in that action that we find out who we are’?”

Cunningham’s words have been a burr in my mind: elders, ancestors, futures, words, action. I have wrapped my life in the stories of others-- those I know and those I do not, those who are famous, infamous, and unknown. Their stories peek out at me from a bookshelf, call to me from verses, and even speak to me as I pour tea from a well used tea pot. Yet I have never considered how in this very moment, I am shaping the story that one day I will pass onto the next generation. I have never imagined that I am my very own story and that my story will impact the living and loving of those who follow me.

In these disorienting times it is difficult to know just how to live our story. How shall we not just post about justice, but act for justice, as C.T. Vivian urges? How will I live as a faithful disciple in a world that has branded Christianity as exclusive? How can I enact inclusive Christianity, and not just think it? My questions have led me back to the same spiritual practice: studying the human story as a road map forward. Every day I am learning how to be a better ancestor, because I am surrounded by my own saints-as-ancestors, and I live in their stories.

We can do the work we are called to do because others before us, like John Lewis, and the less famous Mr. White and Kay, have tilled the soil. For this reason, I will share with you during the coming months snippets of human stories that have shaped me, from famous leaders like John Lewis to unknown saints like Mr. White and Kay, from self-proclaimed Christians to those of other faiths--and those who were unsure of their faith. My hope is that these stories will inspire us to continue the larger human story of progress: of a society that ultimately bends toward a God of love and justice . . . even now, or especially now.

*Please look to "Spirit" tab for the continuation of this blog.

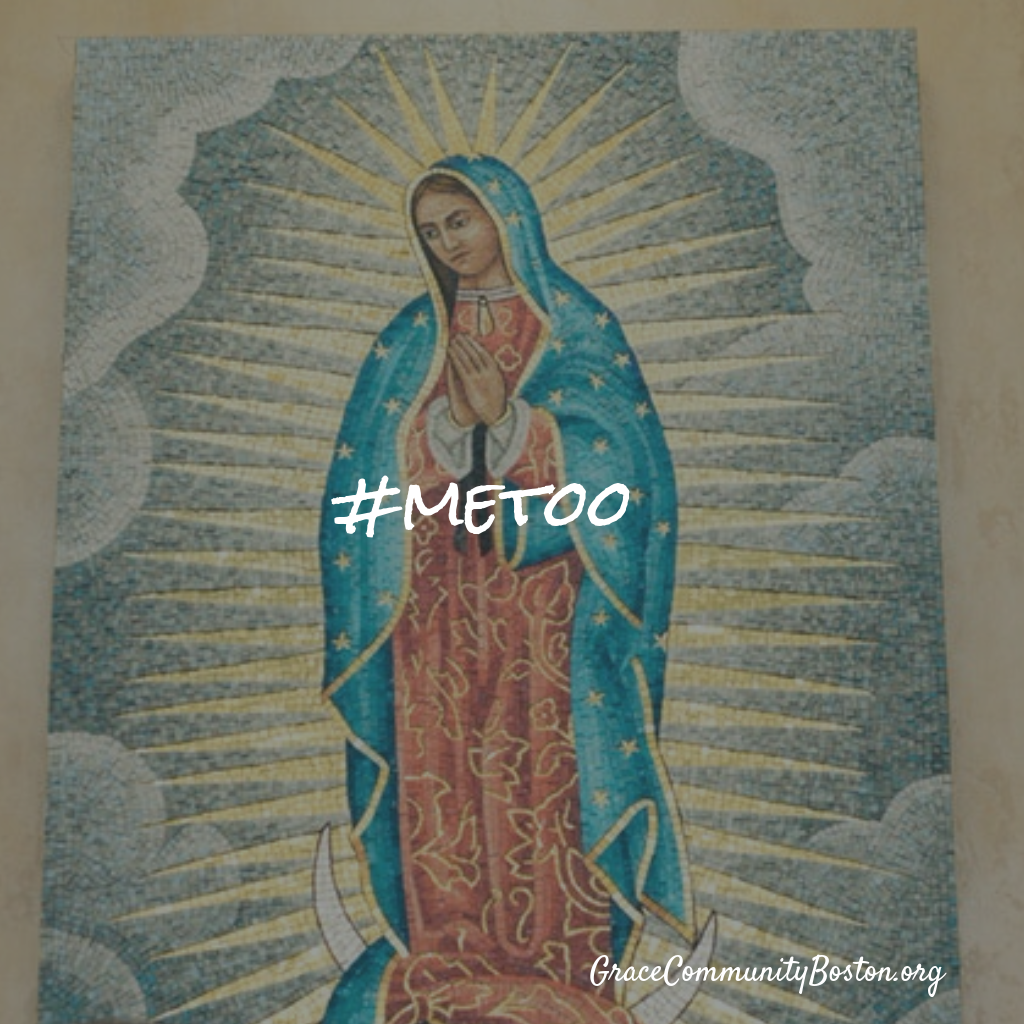

Mary's #metoo Story

I never believed Mary was a virgin. Even before I knew what “virgin” meant, I intuited there was something wrong about the word. My questions regarding Mary’s mysterious virginity were often met with whispers or “we’ll tell you when you’re older.” Later when I knew what the word virgin meant, I rejected that title for Mary even more vehemently. Mothers were a part of my daily life; in my limited experience as a child, mothers were holy regardless of their sexual status. From my own mother to my best friend's mother to the mother of the children I babysat: I knew a mother’s care was unrelated to her sexual proclivity. I suspected Mary loved her child wrapped in swaddling clothes the way all mothers I knew loved their children--deeply and devotedly. I also suspected, and later knew for a fact, that every mother did what the farm animals I saw growing up did. My mother had sex. My best friend’s mother had sex. The woman I babysat for had sex. Mary had to have had sex too. How else would she have become a mother? With no knowledge of IVF and little awareness of adoption, in my young mind, sex was a prerequisite to motherhood. Furthermore, sex did not make motherhood “yucky.” Instead, Hollywood made sex yucky. Therefore, I concluded with certainty: Mary was no virgin.

So why on God’s green earth did the gospel proclaim that Mary was a virgin? Why did the early writers of scripture think it was necessary for Mary to be a virgin? Why couldn't we believe that, like the many women before who had become pregnant, she also became pregnant via sperm and egg, the natural sequence of procreation?

I believe Mary’s pregnancy was undesired, not only by her, but by her community. Undesired (different from unwanted) pregnancies are a common occurrence. Most women unexpectedly find themselves pregnant at some point in their life. Depending on their circumstances these pregnancies range from a welcome surprise, to an inconvenience, to a deeply terrifying predicament. The factors surrounding each pregnancy are different, but for those women who find themselves terrified, it almost always has something to do with power.

In Mary’s time if an unmarried woman was found to be with child there was one course of action: stoning. And there was nowhere to flee, because anywhere she fled, the rules would be the same. Women were the property of their fathers and then their husbands. Mary was without power. So why would Mary risk having sex?

I think that Mary was raped, like so many women before and after her. As a powerless woman, she had no control over her circumstances, no protection from her attacker, no recourse to the law. Instead she was a young girl, betrothed to a man, who found herself confronting a death sentence.

Historically we know that Mary lived in an occupied country. Ancient Palestine was under Roman rule. And if we can draw any inference from other occupied countries, violence was everywhere. Palestine was kept under Roman rule through the terrifying violence of its military. The likelihood that Mary was raped by a Roman soldier is high.

My theory of Mary’s undesired pregnancy is this: like many other powerless women in Ancient Palestine, Mary was raped by a Roman soldier. She just happened to be one of the unlucky ones who became pregnant and could not blame her pregnancy on her betrothed. Thankfully for Mary, Joseph was a magnanimous and compassionate man. He protected Mary, accepted her as his wife, and spared her execution. He broke the rules in order to be kind, as would his son three decades later.

***

So what does this mean about the Christmas story? Does it make Jesus no longer God’s Son? Does it make the whole story a filthy tale of sexual power?

Why would I want to ruin the lovely story of the manger?

I don’t. In fact, I am seeking to create a story more powerful and more consistent with the Gospel. Mary’s story has taken on an entirely new meaning since I have come to believe that she, like many women, was a rape victim.

Mary's #metoo story speaks of a God who can transform violence into something whole. It is a story about the God who turns the crucifixion into the empty tomb. By nature, this same God would transform a violent rape into a magnificent child, with 10 fingers and 10 toes, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. And God did transform the unwanted sexual violence of an abusive occupier into a beloved child. And this child would grow to be a man who preached a redeemed social order-- a social order in which the first would be last, in which the occupier would be powerless.

***

Is this really why the gospel writers chose to call Mary a virgin? Maybe. I can’t be certain, but it seems a perfect way for a male culture to hide the truth. For too long we have been hiding the insidious truth that many men use forced sex to dominate women. We have kept this secret of violence-sex-power for so long we can’t admit that maybe Mary was a victim too. So we’ve embraced her virginity and become complicit. Virginity was more believable than speaking the truth about sexual violence and harassment. But those days are done. The tide of #metoo cannot be held back any longer. And if you think there has been a tidal wave of #metoo confessions, just wait. There's a tsunami coming.

Part of the tsunami is understanding and accepting the story of Mary's pregnancy. Maybe it wasn't a Roman soldier. Maybe it was a neighbor or Mary’s father. Regardless, Mary’s pregnancy was not of her own choosing. Yet the miracle of Jesus’ birth, the wonder of Mary’s courage, the beauty of the manger are not lost. Instead, it is as powerful as the stone rolled away. We are the people of a God who turns stories upside down, who transforms violence into new beginnings, crosses into empty tombs, #metoo stories into babies who grow to preach of an entirely new social order in which the first shall be last.

***

*It is important for me to mention that I am not the first person to suggest that Mary was raped by a Roman soldier. In fact the first time I heard this theory suggested was by Donald Capps, my professor at seminary. But it dates back to Celsus, a second-century Greek opponent of Christianity.

So why on God’s green earth did the gospel proclaim that Mary was a virgin? Why did the early writers of scripture think it was necessary for Mary to be a virgin? Why couldn't we believe that, like the many women before who had become pregnant, she also became pregnant via sperm and egg, the natural sequence of procreation?

I believe Mary’s pregnancy was undesired, not only by her, but by her community. Undesired (different from unwanted) pregnancies are a common occurrence. Most women unexpectedly find themselves pregnant at some point in their life. Depending on their circumstances these pregnancies range from a welcome surprise, to an inconvenience, to a deeply terrifying predicament. The factors surrounding each pregnancy are different, but for those women who find themselves terrified, it almost always has something to do with power.

In Mary’s time if an unmarried woman was found to be with child there was one course of action: stoning. And there was nowhere to flee, because anywhere she fled, the rules would be the same. Women were the property of their fathers and then their husbands. Mary was without power. So why would Mary risk having sex?

I think that Mary was raped, like so many women before and after her. As a powerless woman, she had no control over her circumstances, no protection from her attacker, no recourse to the law. Instead she was a young girl, betrothed to a man, who found herself confronting a death sentence.

Historically we know that Mary lived in an occupied country. Ancient Palestine was under Roman rule. And if we can draw any inference from other occupied countries, violence was everywhere. Palestine was kept under Roman rule through the terrifying violence of its military. The likelihood that Mary was raped by a Roman soldier is high.

My theory of Mary’s undesired pregnancy is this: like many other powerless women in Ancient Palestine, Mary was raped by a Roman soldier. She just happened to be one of the unlucky ones who became pregnant and could not blame her pregnancy on her betrothed. Thankfully for Mary, Joseph was a magnanimous and compassionate man. He protected Mary, accepted her as his wife, and spared her execution. He broke the rules in order to be kind, as would his son three decades later.

***

So what does this mean about the Christmas story? Does it make Jesus no longer God’s Son? Does it make the whole story a filthy tale of sexual power?

Why would I want to ruin the lovely story of the manger?

I don’t. In fact, I am seeking to create a story more powerful and more consistent with the Gospel. Mary’s story has taken on an entirely new meaning since I have come to believe that she, like many women, was a rape victim.

Mary's #metoo story speaks of a God who can transform violence into something whole. It is a story about the God who turns the crucifixion into the empty tomb. By nature, this same God would transform a violent rape into a magnificent child, with 10 fingers and 10 toes, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger. And God did transform the unwanted sexual violence of an abusive occupier into a beloved child. And this child would grow to be a man who preached a redeemed social order-- a social order in which the first would be last, in which the occupier would be powerless.

***

Is this really why the gospel writers chose to call Mary a virgin? Maybe. I can’t be certain, but it seems a perfect way for a male culture to hide the truth. For too long we have been hiding the insidious truth that many men use forced sex to dominate women. We have kept this secret of violence-sex-power for so long we can’t admit that maybe Mary was a victim too. So we’ve embraced her virginity and become complicit. Virginity was more believable than speaking the truth about sexual violence and harassment. But those days are done. The tide of #metoo cannot be held back any longer. And if you think there has been a tidal wave of #metoo confessions, just wait. There's a tsunami coming.

Part of the tsunami is understanding and accepting the story of Mary's pregnancy. Maybe it wasn't a Roman soldier. Maybe it was a neighbor or Mary’s father. Regardless, Mary’s pregnancy was not of her own choosing. Yet the miracle of Jesus’ birth, the wonder of Mary’s courage, the beauty of the manger are not lost. Instead, it is as powerful as the stone rolled away. We are the people of a God who turns stories upside down, who transforms violence into new beginnings, crosses into empty tombs, #metoo stories into babies who grow to preach of an entirely new social order in which the first shall be last.

***

*It is important for me to mention that I am not the first person to suggest that Mary was raped by a Roman soldier. In fact the first time I heard this theory suggested was by Donald Capps, my professor at seminary. But it dates back to Celsus, a second-century Greek opponent of Christianity.