Full Bellies in Boston I am deeply proud of my city, Boston, for an unusual reason. It has nothing to do with one of our famous sports teams. Instead it’s about school lunch: If you attend a Boston public school, regardless of your income, you will receive a free breakfast, snack, lunch, and then final snack if you are in an afternoon program. That is enough calories for a single day, even if you do not have dinner. Many cities provide free meal programs for school children, but there is often a complicated documentation system that places the burden of proof on families. More often than not, school social workers need to track down documents that are never received. Children inevitably slip through the cracks. More complex than documentation: food insecurity cannot be easily calculated on paper. Some children do not qualify who are food insecure. Boston decided in 2013 that full bellies were as important as curriculum. Boston ditched the red tape. All children can eat their fill in the Boston public school system. Then Mayor Thomas Menino said it simply: “Every child has a right to healthy, nutritious meals in school.” He then noted the complications of the application system: “This takes the burden of proof off our low-income families and allows all children, regardless of income, to know healthy meals are waiting for them at school every day.” (BostonPublicSchools.org, BPS Offers Universal Free Meals for Every Child). The church where I serve has partnered with a local school in Boston. The school social worker noticed that children were stuffing their pockets with food on Friday afternoon. And on Monday morning, they couldn’t get enough food into their empty bellies fast enough. Through our food pantry, Rose’s Bounty, we send children home with bags of kid friendly food each Friday to see them through the weekend. Ever since Covid left our city locked down and our school system closed, I have worried and worried about this particular group of children. I have prayed for them, wondering if their bellies ache at night. The city of Boston has done an excellent job, as have many cities, providing food assistance through local community organizations and at central localities. Our church has offered a weekly pop up food pantry in the school recess yard to try and reach families in need. And still we know that there are children who are malnourished because they do not have the consistency of school breakfast and lunch each day. Visible Disparity & Free Lunches When my mom was a child growing up in Buffalo, New York, she walked home everyday for lunch. School lunches were not provided in her neighborhood school, or in most schools in the early 1940s. And without official school lunches, kids could see how hungry each other were. In Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, we see how this wealth disparity plays out during the school lunch. The main character, Scout, comes face to face with poverty for the first time when her older brother, Jem, invites a classmate named Walter home for lunch. At the Finch home, Walter greedily pours molasses all over his meat and vegetables to Scout’s horror. Scout, of course, does not remain quiet. Calpurnia, the Finch’s house keeper and mother of sorts, calls Scout into the kitchen and scolds her for her rude behavior. She explains to Scout that not everyone has as much to eat as Scout. Scout's behavior is not uncommon. I remember vividly bragging about the pot of change my dad left in our kitchen for our school lunches and how my brother and I took however much we wanted (my parents didn’t know this, but they also didn’t monitor). With the extra money we bought ice cream bars and chocolate milk. A classmate was awestruck at this unrestricted access and told me her mother carefully counted out her lunch money each day. My family wanted for nothing; I learned this for the first time at school lunch. Two things happened in America that created the school lunch programs that were the norm when I entered school in 1980. First, women began organizing. It started small, a mother noticing a child with no lunch. These mothers brought children into their homes at the noon hour and made sure they received a filling lunch. This was more common than you can imagine. Soon women were showing up at schools with pots of soup and slices of bread to make sure all the children were fed lunch. Boston led this movement and was the first school district in the country to offer lunches to all students in the late 1890s. The Boston free lunch program was led by the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union. In 1908 in Manhattan, students paid 3 cents or less for pea soup and two slices of bread offered by the Women’s Missionary Society. Second, school lunches became federally supported immediately after World War II. Many young men drafted into World War II couldn’t fight due to malnourishment. Present Truman’s legislative response was simple: the 1946 National School Lunch Act provided affordable meals so kids could grow up to be strong soldiers and strong citizens. The Importance of School Lunches in the Era of Pandemics There are things we simply take for granted. They have been such a part of the common fabric of our communities that we stop noticing. During this pandemic, I have become aware of just how impactful the 1946 National School Lunch Act was on our country. In fact, I have come to realize school lunches are central to our democracy. Let me explain. My rationale is simple. I will confess that although my experience is limited, my work at the Chittick School has given me a bird’s eye view into the terrible domino effects of food insecurity on education. Children can’t learn on empty stomachs. It’s hard for me to imagine anyone disagreeing with this statement. And an educated populace is essential to democracy. As democracy took root in America, public education became not just an ideal, but an imperative. An enlightened public, the founders believed, was essential to self-government. Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Education is the anvil against upon democracy is forged.” If education is essential to self-government, and school lunches are key to children’s ability to learn, then school lunches are central to our democracy. I am not a public health official, and I am not challenging in any way the closure of schools. I do want, however, to offer the following observation: sitting down every day in a cafeteria with classmates, at the same table, in the same room, eating from the same lunch trays, is one of the greatest achievements of our democracy. At that cafeteria moment, we are saying to each child in America, “You matter. Your very physical well being matters. Your education matters. Your voice matters. Your experience matters. Your future matters. You are a citizen of this country and one day we will depend on you to uphold our democracy.” So why does any of this matter to a Christian Disciple? As followers of Jesus, seeking, fighting for, and securing justice is our job description. Sister Simone Campbell said it most clearly when she asserted that salvation is communal. Therefore, justice is how we measure salvation. The measure of justice is how well we do together, as a nation. My salvation is completely tied up with a child sitting down to eat lunch. If that child is hungry, so am I. If I do not fight for justice for that child, I am not closer to salvation. Our destinies are entwined. Jesus called all of his disciples, those who were constantly clueless, those who would deny him, those who would betray him, to eat of bread and drink of cup with him. In that upper room, Jesus made it clear there was only one table and at that table there was room for us all and there was enough for us all. Just as Simone Campbell asserts, Jesus saw salvation as a fully communal endeavor. I like to think of the Boston Public School system’s lunch rooms like Jesus’ table. Everyone is welcome. There is enough for every child. The salvation of each child at each rickety cafeteria table is forever bound up with those who sit across from them, and with me, and with you. Those women who sought free lunches for all children worked not only for our justice, but for my salvation.Thank you.

1 Comment

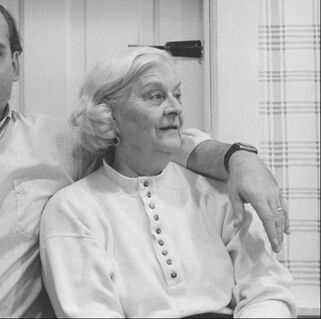

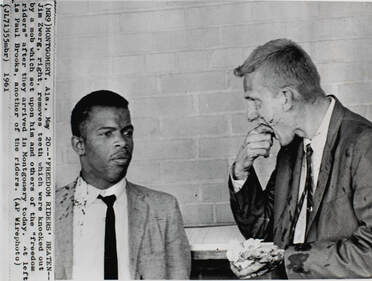

My grandmother would have been 100 years old this month. It doesn’t seem possible. Her name was Edna. We called her grandma Ednut. She was tall and attractive and looked good in jeans and sweaters. She had gorgeous long legs and wore heels anytime she could. She also had the ugliest feet I’ve ever seen. She never had a short old lady hair cut, but instead kept her hair in a swinging bob that framed her striking jaw. After mowing her lawn in the summer, she liked to sit in a lawn chair, overlooking her work, and crack open a cold beer. She cooked for all of us non-stop. Gravy was a beverage. Homemade cookies, as large as saucers, were in the corner of her kitchen at all times. When we visited for a sleepover, we always hit the grocery store (where we were allowed to get anything we wanted) and the butcher (where she made sure we were given “ham off the bone” to nibble on while we waited). But before procuring sustenance, we went to the bank where she withdrew and then counted crisp bills. I was sure she was the richest woman alive. There would also be time spent in her sewing room where she would quickly whip up the prettiest new dresses for our dolls, lace lining the cuffs and hems. I even had a lined pink velvet cape for my favorite figurine. My daughter has this cherished hooded piece in her doll wardrobe today. And if all of this loving attention wasn’t enough my grandmother did more. She showed up at every sports event with chairs, blankets when it was freezing, and juice boxes (before anyone I knew bought them!). She came to Grandparents Day and gave me the correct answers to my spelling test under her breath. She lavished all her grandchildren with love and attention and money! She financed our expensive Victoria’s Secret bras (not my brothers, they didn’t wear bras), interview suits, and much more. She would slip twenties into our pockets for “gas money” before we headed back to college. My grandmother wasn’t perfect. Surprise. She was human. My relationship with her was more fraught the older I got as my views diverged from hers. When she discovered that I had no intention of ever taking my husband’s name she responded, “Who would want to marry you then?!?” Thankfully I had a quick response, “They’re lining up, grandma!” I’m glad Fox news didn’t exist while she was still alive. With time, I have forgotten most of these more difficult things about my Grandma Ednut. Instead, I can still hear her cackle. I delight in telling my children about her. I make things in the kitchen just like she would have, especially her world famous crepes. I received her dining room table, and sit at it every night with my family, feeling her presence. This is how saints are born in our hearts. No life is perfect, but a life lived well graces the imperfections so that the broken bits get left behind. What remains is love. My grandmother loved me wildly, just like she did all her grandchildren. Her love remains a wellspring in my heart to this day. I imagine how she would enjoy my children and, as I imagine this, a silent voice urges me to enjoy, to feed, to care, to laugh, to tend, to love. What greater legacy could we strive for? Happy 100th Grandma Ednut. Your love still blossoms all around us. So may all the saints. "Woman must have her freedom, the fundamental freedom of choosing whether or not she will be a mother and how many children she will have. Regardless of what man's attitude may be, that problem is hers — and before it can be his, it is hers alone. She goes through the vale of death alone, each time a babe is born. As it is the right neither of man nor the state to coerce her into this ordeal, so it is her right to decide whether she will endure it. ― Margaret Sanger, "Woman and the New Race"  Over 100 years ago Margaret Sanger opened the first birth-control clinic in the United States. An advocate for women’s reproductive rights who was also a vocal eugenics supporter, Margaret Sanger has left a complicated legacy — and one that conservative christians have leveraged into sweeping attacks on the organization she helped found: Planned Parenthood. So why would I want to include Margaret Sanger in my blog series about saints? The self-evident reasons are simple: the incredible freedom Sanger offered so many women by teaching us that we do have a choice and that reproductive rights belong to us, not the state or the church. If you want to know about my views on abortion please read my blog, Abortion is Normal, posted on 4/18/2020. Or view the list I created about the ten things you don’t have to believe to be a Christian. There is also a less straightforward reason why I have decided to celebrate Margaret Sanger’s story in this blog series: she had the courage to speak a very uncomfortable truth from her own story. Although her views on eugenics are much more complicated than often presented, I still do not agree with them. Does this disagreement or even dislike mean there is nothing to learn from the radical work of one individual who, against all odds, shifted our world view? Like all the Saints I admire, Margaret Sanger’s very human story shaped her. She grew up as the 6th of 11 children. Her mother conceived 18 times and died at the young age of 49. Sanger was also a nurse who threw herself into difficult and complicated work, tending to the poorest of the poor in New York City. These two factors alone deeply shaped her world view. It is easy to have a distaste for abortion if you have never cared for a mother tending too many children with too little food. It is easy to think God should plan our families when you have access to fresh air and green space and enough work. It is also easy to think that all children are planned by God, even those born with horrid birth defects, when you are not the one listening to them wail in pain with yet another medical procedure. Margaret Sanger witnessed all of this and more. In America, too many of our leaders refuse to speak the truth of their experience. But we have this to learn from Margaret Sanger: speak the unpopular truth of your story. Margaret Sanger knew that if women had access to birth control, then their lives and the lives of their children would radically improve. Today, that truth remains difficult to hear. It is not easy to be faced with the reality that some women lack the material resources to care for their children. It is not easy to face the reality that not all women, maybe even women you know, do not have the emotional bandwidth to be a mother or care for multiple children. Yet this is the truth of many women’s lives and we cannot silence it just because it makes us uncomfortable. Margaret Sanger taught us that speaking our own story’s unpopular truth might free others. She gave women the freedom to choose--to choose their own destiny, to choose their own identity, to choose their own path. Her loving work of liberation makes her a saint, not just for women, but for men as well, and for God.  As those who call ourselves Christian, our new year has actually already begun. It did not begin with the first vaccine injections, and will not begin when the clock strikes midnight on December 31st. Instead, the Christian liturgical year begins the first Sunday we light the advent wreath. This year the beginning of advent was more poignant than ever. During Advent we wait. We wait for the coming of the light as the days grow darker and darker. And the days have grown darker and darker as we are faced with rising infections and covid fatigue and winter closures after a summer and fall of outdoor gatherings. We wait for the end of pain, poverty, and injustice. And this year as we waited death tolls rose, food pantry numbers increased, and racial & social injustice continued to plague our society. We wait for the birth of the Christ Child on Christmas Eve, when busyness will cease, and the familiar carol, O Come All Ye Faithful, fills the church. But this year, there hasn’t been much busyness with holiday parties cancelled and family gatherings postponed. And we will not all be together on Christmas Eve singing in one voice the familiar words: joyful and triumphant! And so we have waited earnestly, impatiently, and sometimes with a well spring of hope, for the child to arrive and transform the darkness. The truth is, we have been waiting since March. We have been waiting for the world to return to normal. We have been waiting to hug those we love and for children to return to school. We have been waiting for familiar routines to envelope us with their predictability. And we have been waiting for a vaccine. Yesterday as I scrolled through my social media feed I was flooded with pictures of friends receiving vaccines: medical professionals and leaders of all kinds. There was electric joy radiating from their faces, sleeves rolled up and ready. Gratitude permeated their written words. The ill timing of Mary’s labor, the swaddling clothes and manger, the chorus of heavenly hosts, the shepherd’s hasty arrival, the wise men’s late arrival -- this story is old to us. It does not hold the same wonder as the new covid vaccine. But perhaps this year, after a year of honing our waiting skills, we will come to understand that a crying infant, born to homeless peasants, is our yearly vaccine. Perhaps this Christmas Eve as we listen at our computer screens or hum O come all ye faithful under our masks, we will awake to the news we have been waiting for all year, and every year. This child born to us, this light, is like an injection of long awaited virus proteins. The antidote the Christ Child offers after all our waiting is this: Hope in the face of fear, Peace in the face of injustice, Joy in the face of heartbreak, and Love, always Love in the face of hate. Thank God for the vaccine and a vulnerable child who reminds us that there is light in the darkness, joyful and triumphant. Amen.  Disclaimer: This blog may feel a whole lot more about me than about the saint I would like to celebrate: Tonya. This may be true. If you can, bear with me. The only way I can express the impact this every day saint has had on the world is through my own experience, particularly what I learned about myself in her presence. And for Tonya: Thank you for letting me share this. How often I pray for you. Tonya and I began Colgate University in the fall of 1994. We had both made it to our first year at college on our own merits you could argue, but looking back I see now what different worlds we came from. I was groomed for private college in every stereo typical way you can imagine. I graduated from an elite private school and was the fourth generation in my family to attend college. I was not only prepared for the academic rigor of college, but also the social expectations which were much more difficult to navigate. When I arrived at Colgate, I felt freed from the social constraints of my prep school. I quickly assessed who was comfortable in that world, which girls had possession of their daddy’s credit cards so they could purchase all the J Crew their hearts desired, and just how the social hierarchy would establish itself. Although I did not possess my daddy’s credit card, I could have tried to establish myself in that unspoken elite circle. I had no interest. I never looked back. Instead, within the first semester, I discovered an ever widening circle of extraordinary 18 years olds, earnestly, if not clumsily, finding their way in the world. Some were prep school kids, others were first generation college students, others were overwhelmed by the demands of the classroom, others aced organic chemistry. It was in one of these ever widening circles that I met Tonya for the first time. Meeting her challenged me to the very core. I wanted to leave the social elitism in which I had marinated for years. I thought I had the moment I walked onto Colgate’s campus. I truly desired to be better than noticing if someone was wearing J Crew or if they had extensive orthodontic work. I yearned to be a real-Jesus-following-inclusive college student. Yes, this sounds overly earnest, but this was my 18 year old self. First let me tell you the person Tonya was the moment I met her: genuine and deeply kind. Engaged in the world around her in such a way that you knew she loved the human race with all of its flaws. She also lacked all the unwritten private school social rules I was used to. She was unapologetically real and almost loud. Not volume loud, but the kind of genuine-eager-engaged loud. There was nothing couth about her. There was also nothing disingenuous about her. Tonya was 100% who she was and lived into the fullness of that person. 25 years later, theologically trained, I would describe her this way: When God called Tonya by name, she heard it loud and clear, greeted God without hesitation, and lived fully into her God-given gifts God, ignoring every challenge, perhaps almost bulldozing right through them. It should also be noted that NO ONE has ever described me as quiet nor demure. So why was I so overwhelmed by Tonya’s genuine engagement with the world. I think it was simple: she was unself- conscious in a way I yearned to be. She was lovingly engaged in the world in a way I sought to be. Tonya's example helped me be less concerned about what people thought of me and more concerned about the impact I had on others. Yes this perhaps sounds simple, but to an 18 year old it was an enormously life changing. At first glance Tonya did not have all of the expensive grooming available to me in prep school world, but at second glance because she was freed from that “grooming” she had discovered the things that truly mattered. Before I met Tonya I thought I didn’t care about such grooming, but my initial reaction to Tonya made me face the truth-- I still did. I wanted to live in both worlds. Yet living in both worlds was not possible if I really wanted to enjoy the freedom of being simply who I was. This was the beginning of a journey, I'm still on (I still am too concerned about what others think of me). I am grateful for the important journey Tonya sent me on: fully embracing the person I was and the person others were regardless of social standards, but instead based on the gifts they shared in relation to others. Tonya is dying of cancer. Her story is unjust. Not long after meeting the love of her life, she was diagnosed with cancer. Recently her trip to Paris was canceled due to COVID. She is now under the care of hospice. She has recently had to stop working which is her calling -- a school psychologist. Yet in all of this I recognize Tonya is still 100% the person she has always been. She is still building community. Her facebook posts are still filled with honesty, thanksgiving, love, heart ache. She is still her authentic “loud” self. This loud self has given others, including myself, permission to live fully into the life given us, genuinely, celebrating the gifts God has given, and always connecting with others. Tonya is a saint. I am positive she would tell me she is not. But she is. A reminder: to be a saint is simple. It means to live in the world in a way in which you leave it is better. I am only one small part of that better world Tonya has created. I am sure there are classrooms of children who can attest to the difference she has made in their lives. Thank you Tonya for being who you are. I am praying and praying that the days you have left are filled with as much joy and love as they have always been.  As promised, here is the first installment: a “snippet” of life to glean hope and inspiration. I begin with John Lewis, the man who inspired this blog series. I was on my parent’s bed. I couldn’t have been older than 11 or 12. The windows were dark, my father was barely awake beside me, the old Philco TV flickered black and white footage from the PBS documentary on the Civil Rights Era, Eyes on the Prize. The first episode I had watched by accident, again beside my half awake father. What I saw viscerally changed me: Emmet Till’s mutilated face. A week later I returned to the series, not for a horror show, but seeking some sort of understanding. What I found was a young, bold man, the Rev. John Lewis. I watched the footage of the Freedom Rides, learned of the angry crowd that greeted Rev. Lewis in Montgomery, the crowd that beat and bloodied him. How did he possess that kind of courage? He answered my earnest question many times throughout his life in interviews and through his public service. The answer is fairly simple: faith. John Lewis began preaching at age 15. His faith propelled him into the heart of the civil rights movement shortly after. At 23 during the March on Washington he spoke from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial as the head of SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee). There, he boldly demanded justice. His fellow Freedom Rider, Jim Zwerg, described John as the one whose faith steadied everyone else: "You knew if you were going to stand with John on a bus platform, John wasn’t going to run. He was going to stand there with you.” This steady, undeterred faith led John from Freedom Rides to the floor of Congress where he fought unrelentingly for justice through gun reform, LGTBQ+ rights, voter protection, education equality and more. John Lewis’ faith was a steady courage fed by worldly hope. He often reminded people that when fighting for justice there would be setbacks, but you had to keep showing up, you had to be consistent. With this dogged persistence you would get there. Hope was not a sentiment to him; it was a discipline for political change. We are on the eve of a referendum in which America will decide who America is: racist or equal, inclusive or exclusive, cruel or kind, just or unjust. John Lewis reminds us that if we are to change the world, we can’t just vote and forget. We must be dogged, not episodic; hopeful, not angry. Above all, we must be grounded in a faith that sustains disciplined hope.  I have been shaped by the human story. My book shelves are stacked with autobiographies. My dining room hutch is adorned with teapots and dishes owned by women who have loved me and are now gone. As a pastor, people share with me their deepest stories. I am forever shaped by these encounters. I have looked for God within the beautiful and terrible, mundane and miraculous, human story. For this reason, I have never read the Bible seeking rules, treating its words as a prescription for how to live. Instead, like a forensic scientist of relationship, I have examined the Bible’s account of individuals and communities for what it means to be human and live fully. I have savored each glimpse into a biblical story that reveals how human love transforms, hate cripples, and desperation guts. I have read and studied all in hopes that I might discover how to live in relationship with God. Brittany Packnett Cunningham wrote in Time magazine after John Lewis’ death: “Our elders become our ancestors ... What kind of ancestors will we be? Daily, the sum of our future ancestry is being totaled. Will we choose mere words? Or, as Lewis compatriot and fellow hero the Rev. C.T. Vivian reminds us, will it be ‘in that action that we find out who we are’?” Cunningham’s words have been a burr in my mind: elders, ancestors, futures, words, action. I have wrapped my life in the stories of others-- those I know and those I do not, those who are famous, infamous, and unknown. Their stories peek out at me from a bookshelf, call to me from verses, and even speak to me as I pour tea from a well used tea pot. Yet I have never considered how in this very moment, I am shaping the story that one day I will pass onto the next generation. I have never imagined that I am my very own story and that my story will impact the living and loving of those who follow me. In these disorienting times it is difficult to know just how to live our story. How shall we not just post about justice, but act for justice, as C.T. Vivian urges? How will I live as a faithful disciple in a world that has branded Christianity as exclusive? How can I enact inclusive Christianity, and not just think it? My questions have led me back to the same spiritual practice: studying the human story as a road map forward. Every day I am learning how to be a better ancestor, because I am surrounded by my own saints-as-ancestors, and I live in their stories. We can do the work we are called to do because others before us, like John Lewis, and the less famous Mr. White and Kay, have tilled the soil. For this reason, I will share with you during the coming months snippets of human stories that have shaped me, from famous leaders like John Lewis to unknown saints like Mr. White and Kay, from self-proclaimed Christians to those of other faiths--and those who were unsure of their faith. My hope is that these stories will inspire us to continue the larger human story of progress: of a society that ultimately bends toward a God of love and justice . . . even now, or especially now.  Warren Buffet’s sister. Know her name? Doris. Buffet, perhaps reclaimed after her many divorces. I’ve added her to my personal saint lexicon, But not for the reason you would think. Not for her philanthropy. She gave away her entire fortune: $200 million and some of her brother’s fortune. Must be fun to have so much money to give away. They called it retail philanthropy. I would call it human connection. Direct small grants to people who need help because sometimes a check really does make a difference. Being poor is awful. Her checks averaged $5,000 and were always accompanied by a letter some included tough love and advice. Imagine how many checks she wrote? 200 million divided by 5k = 40,000 Did she write that many checks with letters to accompany them? “The plan is for my last check to bounce” As a child she was subjected to a daily torrent of emotional abuse. Her mother most likely struggled with an undiagnosed mental health condition. “I decided if there was no fairy godmother for me, maybe I could be one for others.” Some are destroyed by life’s pain and some survive. I don’t know why. I hold no judgment. No advice. I have simply observed long enough as a pastor that this is the truth. Some call it resilience. Others luck. If only we knew the formula that turned the cross into an empty tomb. Doris’ emotional abuse turned into check after check, letter after letter-- a chance for the nameless of the world who perhaps weren’t resilient short on luck no rich brother in the wings. Fairy Godmother. Or saint. I hope she bounced her last check.  This covid-19 shit is real. Yes shit. To be exact: shit show. We call it a shit show at church. Shit show because there were no other words. What are the right words when it comes to a pandemic on top of everything else? The list is long. Forest fires rage. Poverty accelerates with rising unemployment just behind. And we haven't even mentioned #black lives matter. Just this week a black man was shot 7 times in the back while his children watched. Say his name: Jacob Blake. It was with these heavy hearts that we gathered on Zoom. Not outside socially distanced like on Sundays, our folding chairs and water bottles our new church attire. We miss each other's company. We miss each other's physical presence. Still we are truly vulnerable and present with one another on Zoom. The wise woman leading called us simply to share our shit shows. She asked: What is it like for you? What does it feel like? Open ended questions that broke our hearts open. One person confessed that they are so lonely, fighting against depression. The only thing keeping them sane is a beautiful walk. They worry. What happens when they can't take that walk? Another has a stressful job. She is worn out. It’s usually okay, but not on top of everything else. Her mother fell again. Your mother fell again? My dad's dementia is worse now, another adds. Cameras have been placed in his house so they can monitor him. He lost his phone again. They have to get a new one. He needs a better living situation, but who will pay for that? Another confessed he has begun to paint his walls in bright Mexican colors. He can't stand neutral anymore. His loneliness is suffocating him. He doesn't want to give into his depression. It is all too much. He misses seeing his children. He has set his Alexa to remind him every 2 hours to take deep centering breathes. Another just cries. She misses her dad. Her dad has been her rock, her pillar, her life line. She cries because it's a shit show, because there are no other words. What are the right words when it comes to a pandemic? No one has even mentioned school. The endless complications of education. Masks, social distancing, hybrid, not going back, going back, zoom for children? What about those chittick school children? She laments. Those children who have no one to watch them, no one to teach them how to read. No safe space to be nurtured day in and day out. Educational desert. I’m pretty sure I am not going to teach this year, another says. It’s just not safe for me at my age. I’ve yet to make a decision because the school hasn’t made a decision. Living with indecision, in between, liminal space. We lament. We wonder. We get quiet. We hold space for teachers and administrators and kids all at the same time. We know there are no easy answers. A mother sighs, If my kids don't leave this house I'm going to lose it! I can't do it anymore. I can't pick up anymore wet towels. We all need a break from each other! Someone laughs. Someone else laughs. Everyone smiles. Another adds, I'm sure glad I don't have any small kids at home anymore. I don't think we would have made it! It wasn’t all lament. We laughed too, teased each other lovingly. We talked about the Mr. Potato Head. Did you know first there was no plastic potato. You actually used a real potato. Who had an Easy Bake Oven? The shit show is laughter as well. Is the volume turned up more than before? we wonder. It feels like the volume is too loud. There was depression before. There was anxiety before. But now? Just dealing with a pandemic is hard enough. How do we deal with everything else and the pandemic. Talking about shit shows, I had plumbing problems. Me too, someone says. We laugh. We just bought a new house, they explain. I had no idea what it was like to care for a home. Talk about shit shows, her father-in-law is dying. There are no clear answers. If only we could choose our deaths with the snap of a finger. He's had a stroke on top of his congestive heart failure. It's awful. Did you hear so and so fell on her knee at work and is on crutches. Add her to the shit show prayers as well. As if that isn't enough make sure you add those struggling with addiction. Oh yeah and those struggling with mental health. Absolutely. Don't forget the children at the Border in cages. The shit show continues. Don't forget the RNC. All that hate. It's too much. So we pray and we covenant to continue to pray for one another. Because that's who we are. We are a community that vulnerably shares with each other. We surround ourselves in the endlessly loving presence of God and each other. And that love sinks into the mess of our shit shows. We are a shit show church. We say it proudly. Shit show. We say it loudly. Shit show. We say it unapologetically. Shit show. What other word is there to describe what's going on? Nothing. We pray. We are vulnerable. We are human to each other. We are community.  She called for religious absolution. I didn’t need to give it to her, but still she called. Pregnant. She’s not who you think: She’s married. She’s a mother. She’s well educated. She’s successful. She’s pregnant. A lima bean I told her. Not even a lima bean. Not a baby. A mass of cells. 99% effective that birth control! 99%! How can I be the 1%? I’m done having children. I cried when the second pee stick said positive again. She was clear. She doesn’t want another child. Do I have to go to some clinic? No clinic. Go to your doctor. Give thanks you are in a safe state. I am so mad. How can other women not have this choice? Remember, abortion is normal. Normal. They want us to think it’s awful. It’s not awful. It’s a minor medical procedure. You aren’t the first woman who got pregnant on birth control. Abortion is normal. Say this to yourself over and over again. And this is not a gift from God. Thank you for saying that. It isn’t. God didn’t cause COVID-19 to remind us about community. God didn’t decide you should get pregnant so you can love being a mother. We can’t interpret everything as God’s challenge or invitation. Things happen. Cancer. Pandemics. Pregnancy. They aren’t good or bad. They aren’t from God. They just are. Minor medical procedure. Safe. Lima bean. Abortion is normal. You have your life to lead. You matter to God. You are loved. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed